Capital Gains and Losses Investor's Guide to Tax Efficiency

A capital gain is the profit you make from selling an asset for more than you paid for it, while a capital loss is the opposite. For investors in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, understanding these concepts is not just about measuring performance, it’s crucial for navigating complex tax obligations set by bodies like the IRS and HMRC. Mastering capital gains is fundamental to building and preserving long-term wealth.

Summary Table

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Definition | A capital gain or loss represents the difference between an asset’s selling price and its original purchase cost, realized only when the asset is sold. |

| Also Known As | Investment Profit or Loss, Realized Gain or Loss |

| Main Used In | Stock Market, Real Estate, Mutual Funds, Cryptocurrency, Portfolio Tax Planning |

| Key Takeaway | Capital gains are taxable events, while capital losses can offset gains to lower your tax liability. Strategic timing of losses — known as tax-loss harvesting — can optimize returns. |

| Formula | Capital Gain/Loss = Sale Price − (Purchase Price + Associated Costs) |

| Related Concepts |

What is a Capital Gain or Loss

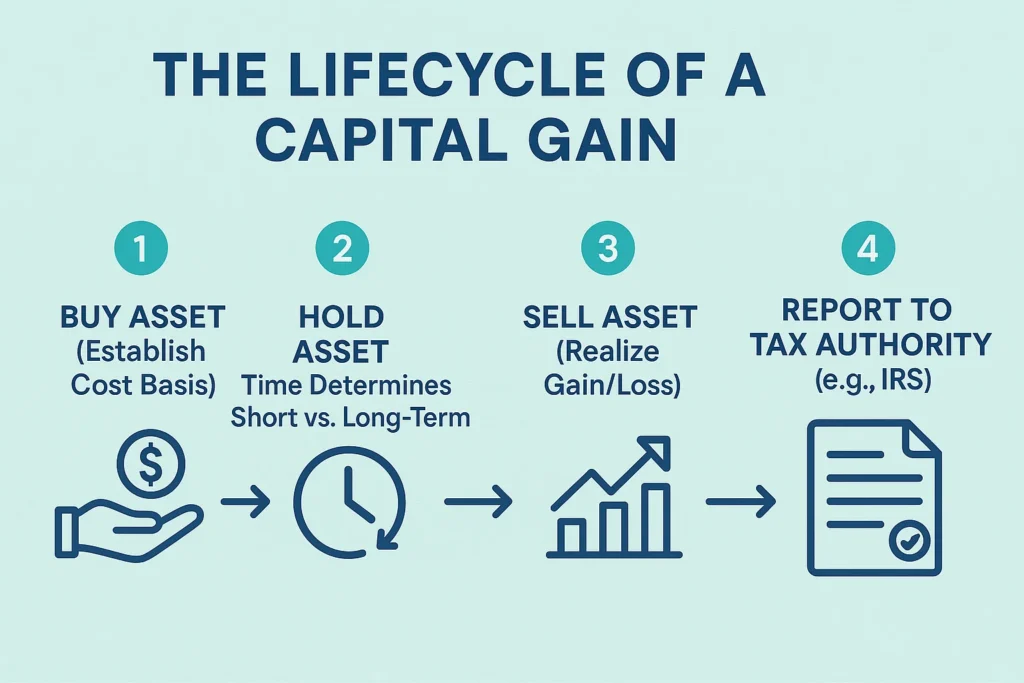

In simple terms, a capital gain or loss is the difference between what you paid for an investment and what you sold it for. The key word here is “realized”, the gain or loss only officially happens, or is “realized,” when you sell the asset. Until then, any increase or decrease in value is called an “unrealized” gain or loss, a paper profit or loss that hasn’t been locked in.

Think of it like this: You buy a vintage comic book for $100. If you sell it a year later for $150, you have a capital gain of $50. If you sell it for $70, you have a capital loss of $30. This simple concept is the foundation for measuring investment performance and, more importantly, for calculating your tax bill.

Key Takeaways

The Core Concept Explained

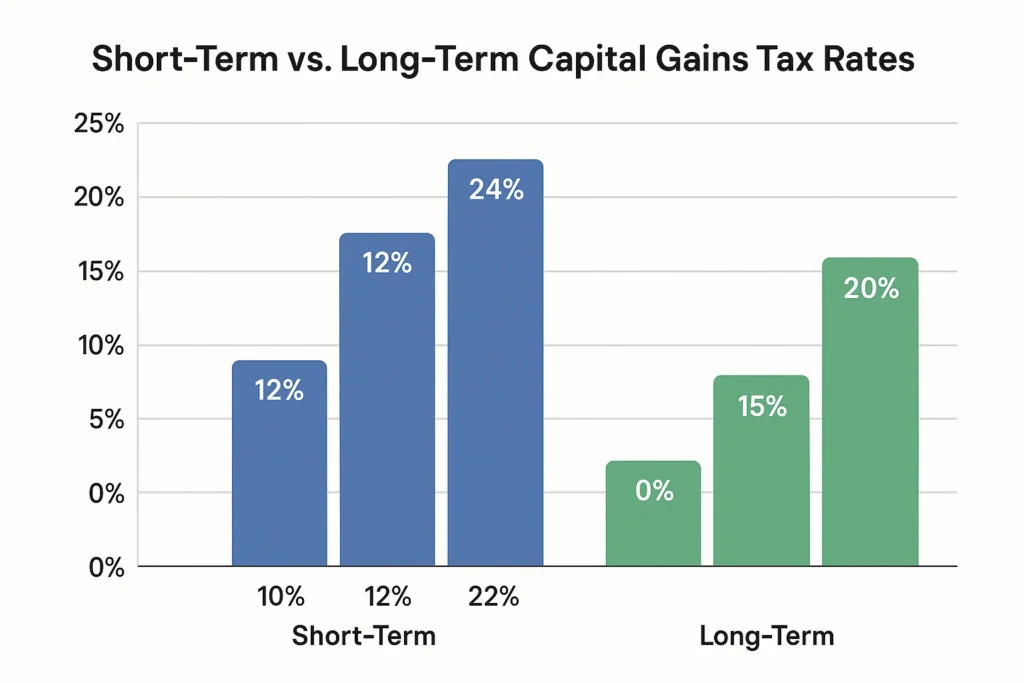

The mechanics revolve around two main factors: the holding period and the cost basis. The holding period determines whether your gain is classified as short-term or long-term, which directly impacts the tax rate you’ll pay. The cost basis is not just the purchase price; it also includes commissions, fees, and other acquisition costs. A higher cost basis means a lower taxable gain (or a higher loss), which is beneficial from a tax perspective.

How to Calculate Capital Gain/Loss

The formula for calculating capital gain or loss is straightforward:

Capital Gain/Loss = Net Sale Price – Adjusted Cost Basis

Step-by-Step Calculation Guide

Let’s break down the components:

- Net Sale Price: The amount of money you receive from the sale, after subtracting any selling commissions or fees.

- Adjusted Cost Basis: The original purchase price of the asset, plus any commissions or fees paid to acquire it, plus any major improvements (for real estate). This is your total investment in the asset.

Example Calculation:

Imagine an investor in the US buys 10 shares of a company listed on the NYSE for $100 per share, paying a $10 brokerage fee. Two years later, they sell all 10 shares for $150 per share, paying another $10 selling fee.

| Input Values | Calculation |

| Purchase Price: 10 * $100 = $1,000 | Net Sale Price: (10 * $150) – $10 = $1,490 |

| Purchase Fee: $10 | Adjusted Cost Basis: $1,000 + $10 = $1,010 |

| Sale Price: 10 * $150 = $1,500 | |

| Sale Fee: $10 | Capital Gain: $1,490 – $1,010 = $480 |

Interpretation: The investor has realized a long-term capital gain of $480. This amount will be subject to long-term capital gains tax rates by the IRS.

Why Capital Gains and Losses Matter to Traders and Investors

- For Investors: Long-term capital gains are central to building wealth through strategies like “buy and hold.” In many Tier-1 countries like the US and UK, they are taxed at a more favorable rate than ordinary income or short-term gains. Understanding this incentivizes long-term thinking.

- For Traders: Active traders need to meticulously track their gains and losses to understand their true profitability after fees and taxes. A high volume of short-term trades can lead to a significant tax burden, as these are typically taxed at higher, ordinary income rates.

- For Portfolio Management: Capital losses are not just setbacks; they are tools. You can use them to offset capital gains in a strategy known as tax-loss harvesting, which can improve your portfolio’s after-tax returns. For more on this, see the IRS Topic No. 409 on Capital Gains and Losses.

How to Use Capital Gains/Losses in Your Strategy

Use Case 1: Tax-Loss Harvesting

At the end of the tax year, you review your portfolio and see a stock that has an unrealized loss. You can sell it to realize the loss, which can then be used to offset gains you’ve made from selling other winners. This lowers your overall taxable income. Just be aware of the wash-sale rule, which prevents you from claiming a loss if you buy a “substantially identical” asset 30 days before or after the sale.

Use Case 2: Strategic Selling for Retirement

An investor nearing retirement might strategically sell assets held for over a year to realize long-term gains. If they are in a lower income bracket in retirement, they might pay 0% on those gains, a powerful income-planning tool.

Use Case 3: Rebalancing a Portfolio

When rebalancing your portfolio, you might need to sell assets that have performed well. Being conscious of the holding period can help you decide which shares to sell (e.g., those held long-term for a lower tax rate) to minimize the tax impact of rebalancing.

To efficiently track your cost basis and realized gains, you need a brokerage with excellent reporting tools. We’ve reviewed the best platforms for active investors to help you choose.

- Tax Advantage: Long-term holdings often enjoy lower tax rates, encouraging patient investing.

- Loss Harvesting: Capital losses can offset gains, lowering overall tax liability.

- Wealth Building: Deferring taxes on unrealized gains allows compounding to work more efficiently over time.

- Timing Control: Investors can decide when to realize gains, optimizing tax timing and cash flow.

- Complex Rules: Determining cost basis and tracking adjustments can be tedious for active traders.

- Higher Short-Term Taxes: Short-term gains are taxed at ordinary income rates, reducing profit.

- Wash Sale Rule: Disallows loss claims if you repurchase the same asset within 30 days.

- Policy Uncertainty: Tax benefits depend on current laws, which may change with new regulations.

Capital Gains in the Real World: A Case Study

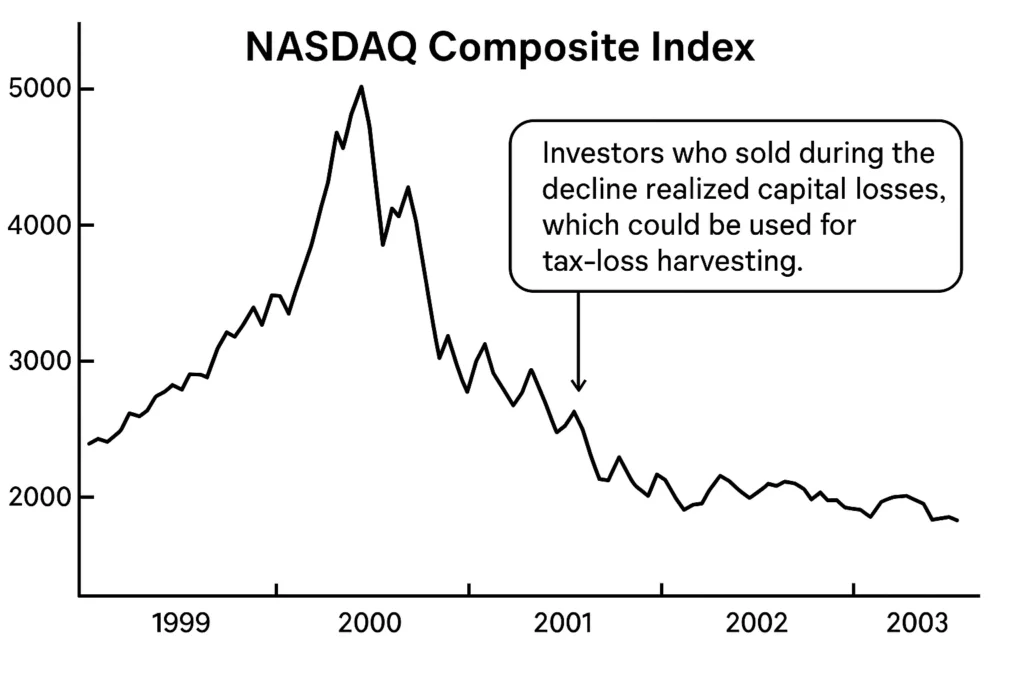

The Dot-Com Bubble and Tax-Loss Harvesting

The early 2000s dot-com crash provides a classic, albeit painful, case study. Many investors who bought tech stocks on the NASDAQ at peak valuations in 1999 and 2000 saw their portfolios plummet by 2002.

An investor who bought $10,000 of a popular tech ETF at the peak might have seen it fall to $2,000. By selling, they would realize an $8,000 capital loss. While this sale locks in a loss, that $8,000 loss could then be used to offset $8,000 in capital gains from other, profitable investments they sold that year.

If they had no gains to offset, they could use up to $3,000 of the loss to reduce their ordinary income, carrying the remaining $5,000 forward to future tax years. This strategic use of a bad situation helped many investors recover more quickly by lowering their immediate tax burden, freeing up capital to reinvest.

The Investor’s Mindset: Dealing with Gains and Losses

Many investors fall prey to cognitive biases that can hurt their returns.

- The Disposition Effect: This is the tendency to sell assets that have increased in value (winners) too early, while holding on to assets that have decreased in value (losers) for too long. People are quick to lock in gains to feel a sense of success but are reluctant to realize losses because it makes the failure feel real.

- How to Overcome It: Base your sell decisions on fundamentals and strategy, not emotion. Ask yourself: “If I didn’t already possess this losing stock, would I purchase it today at this value?” If the answer is no, it might be time to sell and realize the loss for tax purposes, turning a psychological negative into a strategic positive.

Beyond the Basics: Choosing Your Cost Basis Method

If you’ve bought shares of the same stock at different times and prices, you have choices when you sell. The method you choose can impact your tax bill.

- FIFO (First-In, First-Out): The default method for most brokers. The first shares you bought are the first ones sold. This often results in selling long-term shares with the lowest cost basis, leading to a larger taxable gain.

- Specific Identification (SpecID): This advanced method allows you to select the specific shares you want to sell. This gives you maximum control. You can choose to sell the shares with the highest cost basis to minimize your current gain, or sell shares that have just passed the one-year mark to qualify for the long-term rate.

- Actionable Tip: Contact your broker to ensure your account is set up for SpecID and learn how to use it when placing a trade. This is a powerful tool for active tax management.

Realized Gains/Loss vs Unrealized Gain/Loss

A common point of confusion is the difference between Realized and Unrealized Gain/Loss.

| Feature | Realized Gain/Loss | Unrealized Gain/Loss |

|---|---|---|

| When it occurs | Occurs when you sell the asset and lock in profit or loss. | Exists only while holding the asset without selling it. |

| Tax Implications | Taxable if it’s a gain; reportable for the tax year of sale. | No immediate tax effect until the asset is sold. |

| Impact on Cash | Affects your cash flow once proceeds are received. | Purely a “paper” change in value; no cash movement yet. |

| Also Known As | Locked-in Profit/Loss. | Paper Profit/Loss. |

Conclusion

Understanding capital gains and losses provides the foundation for intelligent, tax-efficient investing. While the core concept is simple, profit or loss on a sale, its implications for your portfolio’s after-tax returns are profound. As we’ve seen, they offer significant advantages like preferential tax treatment and the power of tax-loss harvesting, but also come with caveats like complexity and the wash-sale rule. By consciously incorporating an awareness of capital gains into your investment strategy, choosing holding periods wisely and using losses strategically, you move from being a passive investor to an active manager of your financial future. Start by reviewing your portfolio’s unrealized gains and losses today.

Ready to build a tax-smart investment portfolio? The right brokerage can make all the difference. Explore our in-depth reviews of the Best Online Brokers for Long-Term Investors to find a platform that offers robust tax reporting and tools.

Related Terms

- Cost Basis: The total amount you have invested in an asset, including purchase price and fees.

- Tax-Loss Harvesting: The approach of trading assets at a loss to offset capital gains tax accountability.

- Wash Sale Rule: An IRS rule that disallows a loss claim if the same stock is repurchased within 30 days.