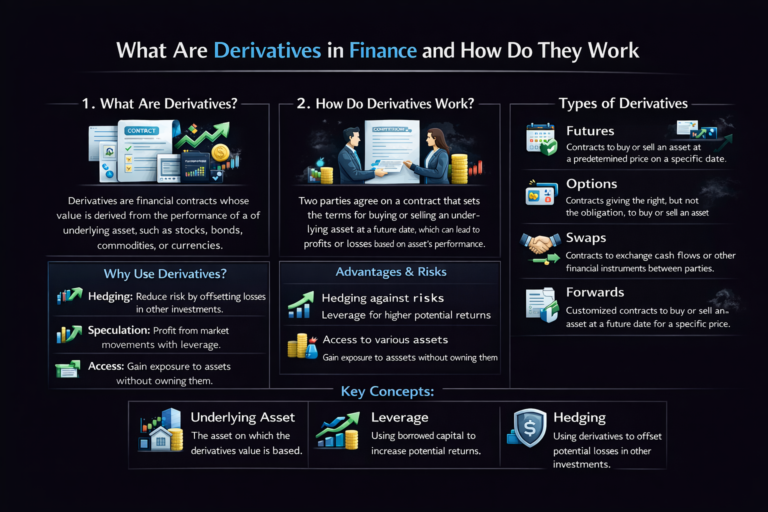

What Is Deflation, Why Its Risky, How to Prepare For It

Deflation is a sustained and general decline in the price level of goods and services within an economy. Often mistaken for a simple “good deal,” it’s a powerful economic force that can signal deep distress, erode corporate profits, and increase the real burden of debt. For investors in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, understanding deflation is critical to protecting capital during rare but impactful economic downturns.

Summary Table

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Definition | A sustained decrease in the general price level of goods and services in an economy, increasing the purchasing power of money. |

| Also Known As | Negative Inflation, Price Decline |

| Main Used In | Macroeconomics, Central Banking, Bond & Equity Analysis, Economic Forecasting |

| Key Takeaway | While falling prices sound beneficial, deflation often triggers a vicious cycle of reduced spending, lower profits, job cuts, and economic contraction, making it a central banker’s nightmare. |

| Formula | N/A (Measured by negative Consumer Price Index (CPI) or GDP Deflator growth rates) |

| Related Concepts |

What is Deflation

Deflation is more than just a seasonal sale or a drop in the price of a single product like electronics. It’s a broad-based, persistent decline in the overall price index—such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or the GDP deflator—across the entire economy. This means your dollars, pounds, or euros can buy more over time. While this sounds like a consumer’s dream, it’s typically a symptom of serious economic imbalance. It often arises from a collapse in aggregate demand (people and businesses stop spending), a surge in productivity that outpaces wage growth, or a severe contraction in the money supply. Central banks, like the Federal Reserve or the Bank of England, fear deflation more than moderate inflation because its dynamics are harder to reverse.

Key Takeaways

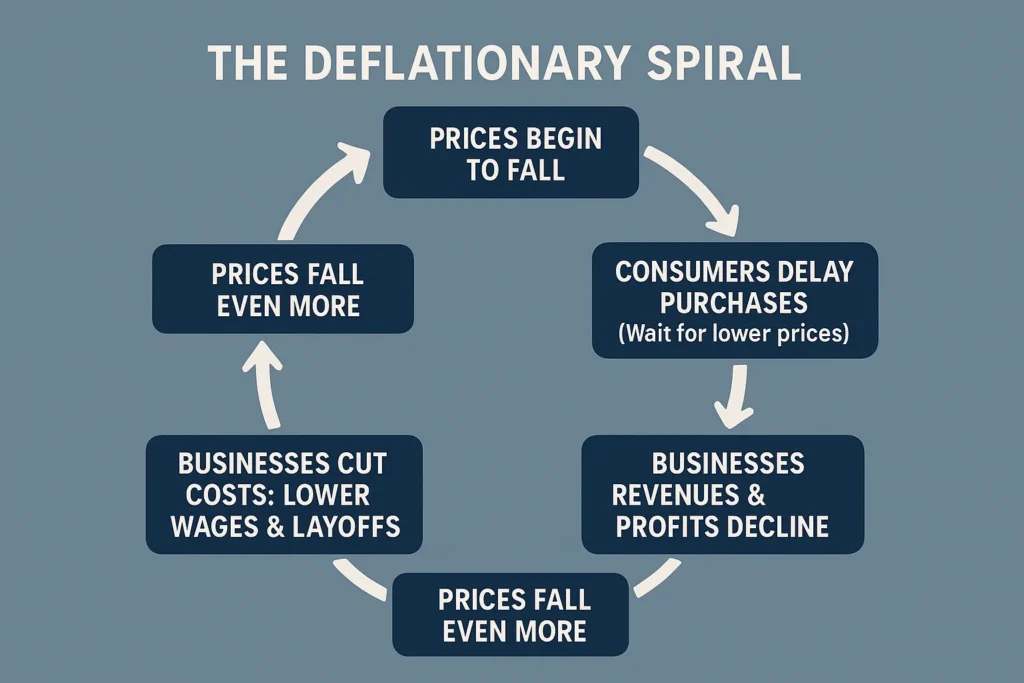

The Core Concept Explained

At its heart, deflation represents a fundamental imbalance between the supply of goods/services and the demand for them, often coupled with a shrinking money supply. Imagine an economy where everyone is fearful of the future. Consumers postpone buying a new car or renovating their home because they believe it will be cheaper in six months. This drop in consumer spending hits corporate revenues. Businesses, facing declining sales, are forced to slash prices to attract customers. Their profit margins evaporate. To survive, they halt investment, freeze hiring, and lay off workers. The newly unemployed spend even less, reinforcing the initial drop in demand. This is the dreaded deflationary spiral.

Furthermore, in a deflationary environment, holding onto cash becomes a winning strategy because its purchasing power increases automatically. This incentivizes hoarding money rather than investing it in productive assets, starving the economy of the credit and investment needed for growth. It’s a trap where prudent individual behavior (saving more, spending less) leads to a collectively worse outcome for the entire economy.

How is Deflation Measured

Deflation itself isn’t “calculated” via a single formula but is identified as a sustained negative growth rate in a broad price index. The process is identical to measuring inflation, but the result is below zero.

The Measurement Process

- Select a Price Index: Economists primarily use:

- Consumer Price Index (CPI): Tracks the price of a basket of consumer goods and services. This is the most common headline measure. (e.g., US Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI, UK Office for National Statistics CPI).

- GDP Deflator: A broader measure that reflects the prices of all domestically produced goods and services.

- Producer Price Index (PPI): Measures prices at the wholesale level, often a leading indicator for future consumer inflation/deflation.

- Calculate the Period-over-Period Change: The inflation/deflation rate is the percentage change in the index value over a specific period (usually year-over-year).

- Formula: ((Current Period Index – Previous Period Index) / Previous Period Index) * 100

- Interpret the Sign: A negative result indicates deflation.

Example Calculation:

Let’s say the CPI for the United States was 300.0 in January 2023 and 294.0 in January 2024.

- Input Values: Current CPI = 294.0, Previous CPI = 300.0

- Calculation: ((294.0 – 300.0) / 300.0) * 100 = (-6.0 / 300.0) * 100 = -2.0

- Interpretation: The economy experienced a 2.0% deflation rate over that year. This means, on average, the purchasing power of the US dollar increased by 2%, but it also signals a contracting price environment with potentially negative economic consequences.

Why Deflation Matters to Traders and Investors

Understanding deflation is not an academic exercise; it’s a crucial component of macroeconomic analysis that directly impacts asset allocation and risk management.

- For Investors (Long-Term): Deflation reshapes the entire investment landscape. Equities typically suffer as corporate earnings collapse. “Growth” stocks with high future earnings expectations are hit hardest, while companies with strong balance sheets, minimal debt, and stable cash flows (e.g., certain consumer staples, utilities) may hold up better. Long-dated government bonds (like US 10-year Treasuries) become prized assets, as their fixed coupon payments become more valuable in real terms, driving bond prices up and yields down.

- For Traders (Short-Term): Traders watch for deflationary signals (like consecutive negative CPI prints, plunging commodity prices like oil, or a soaring US Dollar Index (DXY)) to position themselves. This might mean shorting cyclical sectors (e.g., industrials, materials), going long on the USD against other currencies, or buying Treasury futures. The volatility in bond markets can present significant opportunities.

- For Analysts & Economists: Deflation changes valuation models. The discount rate used in Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) models may need adjustment, and terminal growth assumptions become problematic. Analysts must scrutinize company debt levels obsessively, as deflation turns debt into a crushing burden.

How to Navigate Deflation in Your Investment Strategy

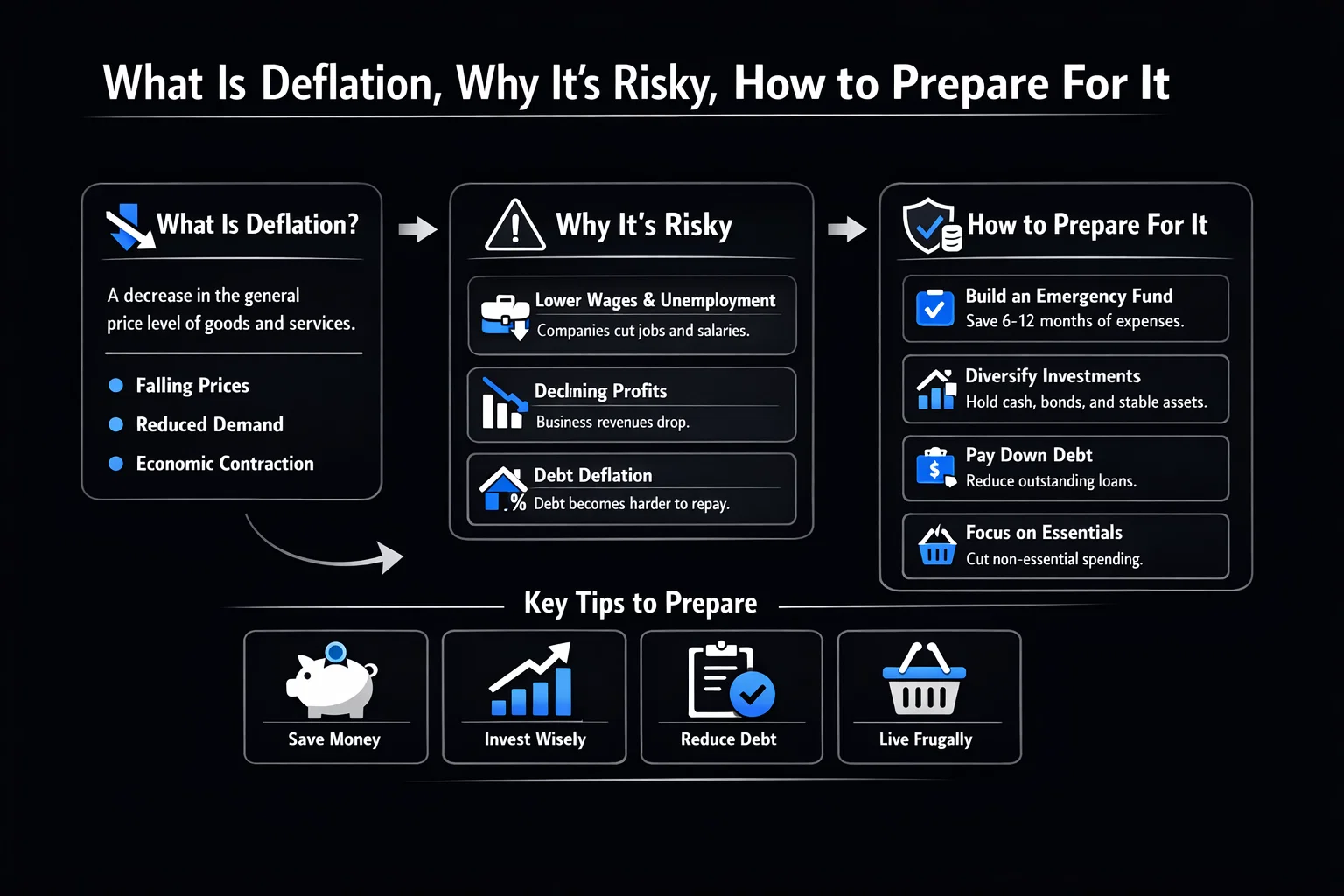

While hoping to avoid a deflationary era, prudent investors can prepare and adjust.

- Case 1: Defensive Portfolio Rebalancing: When leading indicators (PPI, commodity bust, yield curve inversion) point to deflation risk, increase allocation to high-quality government bonds (US Treasuries, UK Gilts, German Bunds). Reduce exposure to highly leveraged companies and cyclical stocks. Consider increasing cash holdings for both safety and future buying opportunities.

- Case 2: The “Debt Trap” Screen: Use fundamental screening tools to identify and avoid companies with weak interest coverage ratios or high debt-to-equity levels. These firms are most vulnerable in a deflationary environment. Resources like the SEC’s EDGAR database or the London Stock Exchange website are essential for this analysis.

- Case 3: Currency Plays: Deflation often strengthens a currency due to increased purchasing power and safe-haven flows. Monitoring pairs like USD/JPY or USD/EUR can reveal trends. For instance, Japan’s experience with deflation has often seen the Yen strengthen.

- Case 4: Watching for Policy Response: The biggest market moves often come from central bank actions. Announcements of massive quantitative easing (QE) by the Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank (ECB) can sharply reverse deflationary trends in asset prices, creating pivotal trading moments.

To implement these defensive screens and rebalancing acts, you need a brokerage platform with robust research and screening tools. We’ve analyzed the top platforms for long-term, defensive investors to help you choose the right one.

A Sector-by-Sector Analysis

Not all investments suffer equally during deflation. Understanding which sectors are most vulnerable—and which might even benefit—can help you build a more resilient portfolio. Here’s a comprehensive breakdown of how major sectors typically perform during deflationary periods.

Sectors Most Exposed to Deflation

Financials & Banking

High Risk- Debt defaults surge as real debt burdens increase

- Loan portfolios deteriorate rapidly

- Net interest margins compress in low-rate environment

- Potential for bank runs in severe cases

Consumer Discretionary

High Risk- First expenses cut from household budgets

- Big-ticket purchases (cars, appliances) postponed indefinitely

- High operating leverage magnifies profit declines

- Inventory becomes worth less daily

Real Estate

High Risk- Property values decline with general price level

- Rents fall as tenants renegotiate or vacate

- High debt levels become crushing burden

- Commercial vacancies rise as businesses fail

Sectors That Often Hold Up Best

Consumer Staples

Lower Risk- Non-discretionary demand (food, toiletries)

- Pricing power for essential goods

- Stable cash flows support dividends

- Discount retailers may actually benefit

Utilities

Lower Risk- Regulated monopolies with stable demand

- Rate adjustments may lag but are predictable

- High dividend yields become more attractive

- Essential service regardless of economy

Healthcare (Non-Elective)

Lower Risk- Medical needs don’t disappear in downturns

- Government and insurance payments provide stability

- Demographics (aging populations) support demand

- Essential pharmaceuticals maintain demand

Sectors with Mixed or Contrarian Opportunities

Technology

Selective- Vulnerable: Hardware, consumer electronics, discretionary software

- Resilient: Productivity software, cybersecurity, cloud infrastructure

- Companies with strong cash balances survive better

- “Good deflation” from tech advances can help some players

Industrials

Selective- Vulnerable: Cyclical capital goods, construction equipment

- Resilient: Defense contractors, maintenance/service businesses

- Government spending can offset private sector weakness

- Companies serving essential infrastructure fare better

Cash-Rich Companies

Opportunity- Cash becomes more valuable during deflation

- Can acquire distressed competitors at fire-sale prices

- No debt burden to service with shrinking revenues

- Can maintain dividends when others cut

Strategic Implications for Portfolio Construction

Defensive Rotation

Shift from cyclical growth stocks to defensive, dividend-paying stocks in resilient sectors. Quality matters more than growth potential.

Balance Sheet Analysis

Scrutinize debt levels obsessively. Companies with strong balance sheets become survivalists; leveraged companies become casualties.

Sector Weighting

Consider underweighting financials and consumer discretionary while overweighting staples, utilities, and healthcare in deflationary environments.

- Purchasing Power Boost: For savers and those on fixed incomes, the value of cash increases, allowing it to buy more.

- Drives Efficiency: Forces businesses to eliminate waste and innovate to survive, potentially raising long-term productivity.

- Cools Speculation: Makes holding cash attractive, which can prevent or puncture dangerous asset price bubbles.

- Lower Import Costs: If the domestic currency strengthens due to deflation, imported goods become cheaper for consumers.

- The Vicious Spiral: Can trigger a self-reinforcing cycle of falling demand, prices, profits, and employment that is hard to stop.

- Crushing Debt Burden: Increases the real value of debt, leading to defaults, bankruptcies, and banking crises.

- Paralyzes Monetary Policy: Renders traditional interest rate cuts useless at the “zero lower bound,” forcing risky unconventional measures.

- Stifles Investment: Why invest in a new factory if the output will be worth less in the future? This hampers long-term economic growth.

Deflation in the Real World: The Case of Japan’s “Lost Decades”

The most stark modern example of persistent deflation is Japan from the mid-1990s through the 2010s. Following the collapse of a massive real estate and stock market bubble in 1991, Japan entered a prolonged period of economic stagnation and deflation.

- What Happened: Asset prices crashed, leaving banks with bad loans and consumers and companies deeply in debt. As prices began to fall, consumers postponed spending. Companies faced a “liquidity trap” – even with interest rates near zero, they didn’t want to borrow to invest in a shrinking economy.

- The Impact: Japan’s Nikkei 225 stock index fell from nearly 39,000 in 1989 to around 8,000 in 2009. The economy experienced near-zero growth and recurring deflation for over 15 years. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) became a pioneer in unconventional policy, launching aggressive quantitative easing long before the Federal Reserve or ECB.

- The Lesson: It demonstrated how difficult it is to escape deflation once expectations become entrenched. It showed the limits of monetary policy and the importance of aggressive, pre-emptive fiscal stimulus. For investors, it was a lesson in the outperformance of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) and the long-term underperformance of equities during such a period.

The Textbook Deflation: America’s Great Depression

While Japan’s “Lost Decades” provide a modern example, the Great Depression of the 1930s remains the most severe deflationary crisis in modern history. Understanding this period is crucial, as it shaped modern economic policy and gave us the very theory of “debt-deflation.”

The Perfect Deflationary Storm

Stock Market Crash & Initial Shock

The Dow Jones Industrial Average lost nearly 90% of its value from peak to trough. Wealth evaporated overnight, destroying $14 billion in value (about $206 billion today). This immediate wealth destruction caused consumers and businesses to sharply curtail spending.

Policy Mistakes Amplify the Crisis

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (1930) raised import duties, triggering international retaliation and collapsing global trade by 65%. The Federal Reserve, following the gold standard orthodoxy, raised interest rates to defend the dollar, exactly the wrong move during deflation.

Banking Collapse & Debt Deflation

As prices fell 10% annually, the real value of debt soared. Farmers and businesses defaulted en masse. Bank runs became commonplace, with depositors losing $1.3 billion. This credit contraction strangled the economy further, creating Fisher’s “debt-deflation” spiral in action.

The Fisher Debt-Deflation Theory Emerges

Economist Irving Fisher observed the crisis firsthand and developed his seminal theory. He described the nine-step process:

- Debt liquidation leads to distress selling

- Contraction of deposit currency as bank loans are paid off

- A fall in the level of prices

- A still greater fall in business net worth

- A fall in profits

- A reduction in output, trade, and employment

- Pessimism and loss of confidence

- Hoarding of money

- Complicated disturbances in interest rates

This theory became the foundation for understanding why deflation is so difficult to escape once it takes hold.

Why This Still Matters for Today’s Investor

The Great Depression led to three revolutionary changes that affect every modern investor:

- The New Deal & Fiscal Policy: Established that government must intervene during deflationary crises through spending (Keynesian economics).

- Banking Regulation: Created the FDIC (1933) and Glass-Steagall Act, fundamentally changing bank risk and investor confidence.

- Federal Reserve Evolution: The Fed’s failure during the Depression led to its modern dual mandate of price stability AND maximum employment.

Key Takeaway: The policy tools created in response to the Great Depression—deposit insurance, lender-of-last-resort functions, and countercyclical fiscal policy—are the very tools central banks and governments would deploy in any future deflationary crisis.

Deflation vs Disinflation

| Feature | Deflation | Disinflation |

|---|---|---|

| Price Trend | Prices are falling (negative inflation rate). | Price rises are slowing, but still positive. |

| Economic Growth | Typically very low or negative (recession). | Can be positive or negative; not directly linked. |

| Primary Cause | Collapse in aggregate demand, debt overhang. | Tighter monetary policy, easing supply chains. |

| Central Bank Stance | Aggressive stimulus (QE, low rates). | May pause or slow the pace of interest rate hikes. |

Conclusion

Ultimately, understanding deflation is not about anticipating a common event, but about preparing for a high-impact, low-probability risk that can devastate unprepared portfolios. While its apparent benefit of cheaper prices is seductive, its underlying mechanics—the deflationary spiral, the debt trap, and policy impotence—make it a paramount concern for central banks and a critical factor in strategic asset allocation. By recognizing its early signals, adjusting your portfolio towards high-quality bonds and companies with pristine balance sheets, and understanding the potential policy responses, you can navigate a deflationary environment with greater resilience. Start by incorporating a review of inflation/deflation trends and corporate debt levels into your regular investment research routine.

Ready to build a portfolio that can weather any economic climate, including deflation? The foundation is a reliable, low-cost brokerage with access to global bonds and rigorous screening tools. Explore our independent guide to the best platforms for defensive, long-term investing to take the next step.

Related Terms

- Inflation: The opposite phenomenon – a sustained increase in the general price level. Understanding one requires understanding the other.

- Quantitative Easing (QE): The primary unconventional monetary tool used to combat deflation and the zero lower bound.

- Liquidity Trap: A situation where interest rates are near zero, savings are hoarded, and monetary policy becomes ineffective – often associated with deflation.

- Consumer Price Index (CPI): The key metric used to measure inflation and deflation.

Frequently Asked Questions About Deflation

Recommended Resources

- For primary data and policy statements, visit the Federal Reserve’s website on monetary policy, the Bank of Japan’s extensive materials on fighting deflation, or the Bank of England’s inflation reports.

- Bookmark the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) CPI page and the OECD’s inflation data portal for cross-country comparisons.

- “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions“ by Irving Fisher (1933) is the seminal academic paper on the topic. While dense, it’s the source of the core concepts.