What Is Financial Crash, Causes, How to Protect Your Money

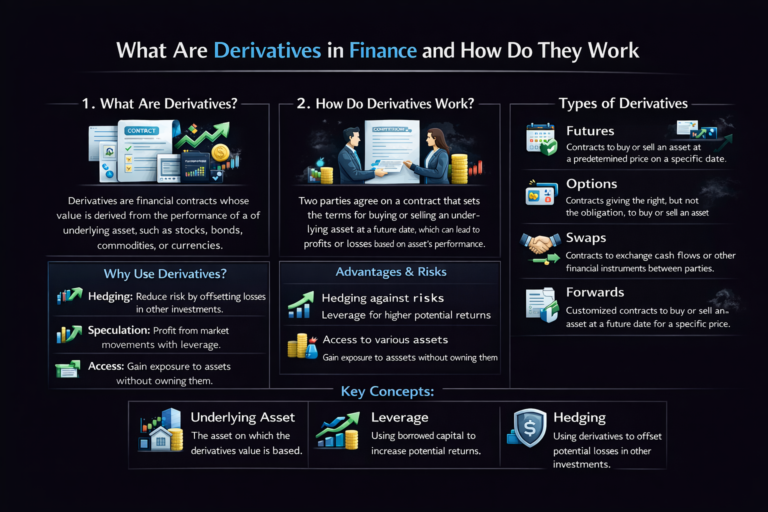

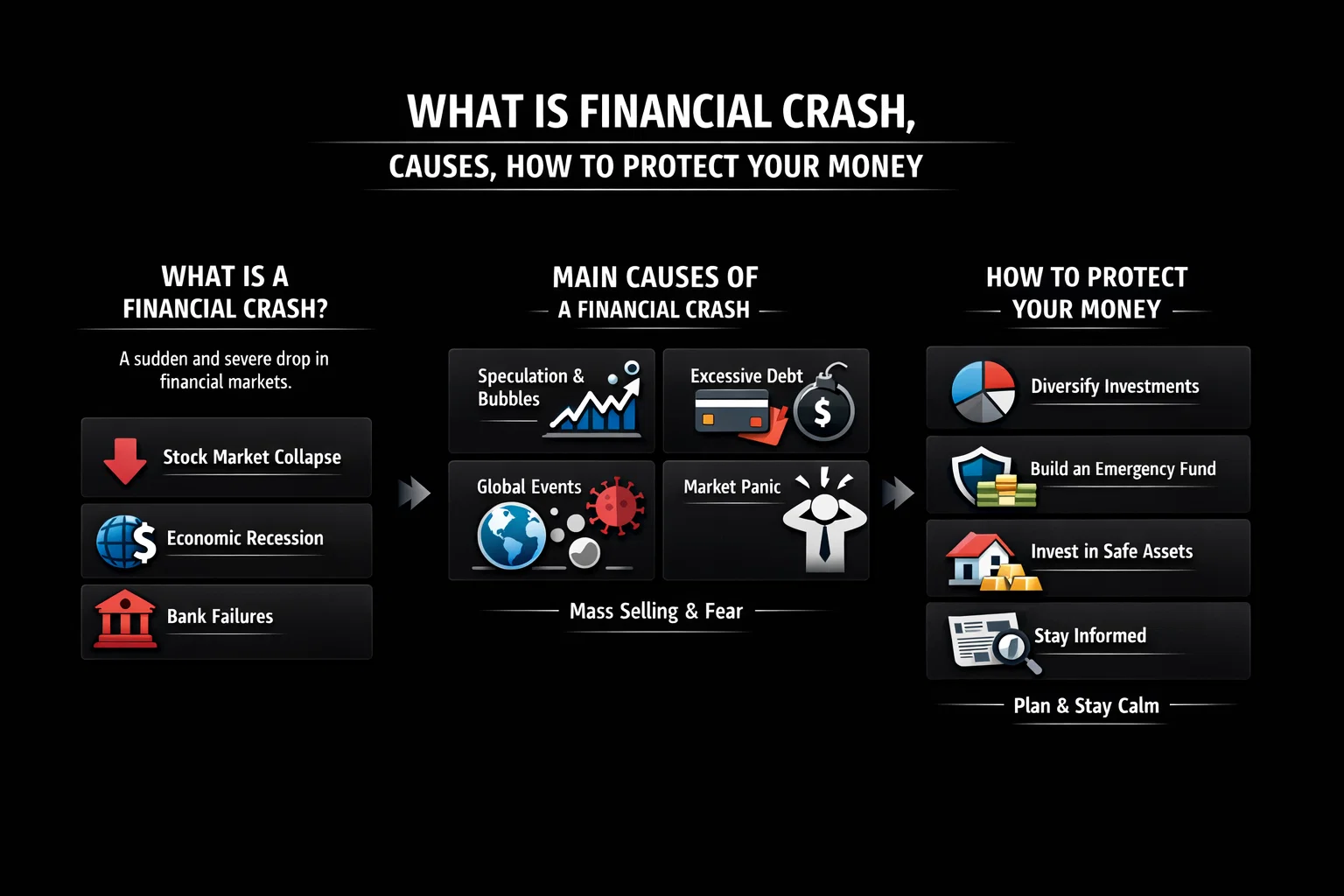

A financial crash is a sudden, dramatic, and widespread collapse of asset prices and market confidence, leading to severe economic dislocation. It represents the catastrophic failure of a speculative bubble or an over-leveraged system, where fear overtakes greed. Understanding the anatomy of a crash is crucial for any investor looking to preserve capital and navigate extreme market volatility.

For investors in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, the specter of a crash looms over major exchanges like the NYSE, NASDAQ, FTSE, and ASX, making knowledge of historical patterns and defensive strategies a key component of financial resilience.

Summary Table

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Definition | A rapid, severe, and broad decline in the value of financial markets or assets, typically exceeding 20% in a short period, characterized by panic selling and a loss of liquidity. |

| Also Known As | Market Crash, Stock Market Crash, Financial Meltdown, Panic |

| Main Used In | Macroeconomic Analysis, Risk Management, Financial History, Portfolio Hedging |

| Key Takeaway | Financial crashes are rare but devastating events often caused by a confluence of speculation, leverage, and external shocks; their primary risk is permanent capital loss, making preparedness non-negotiable. |

| Formula | N/A (Qualitative/Quantitative Identification) |

| Related Concepts |

What is a Financial Crash

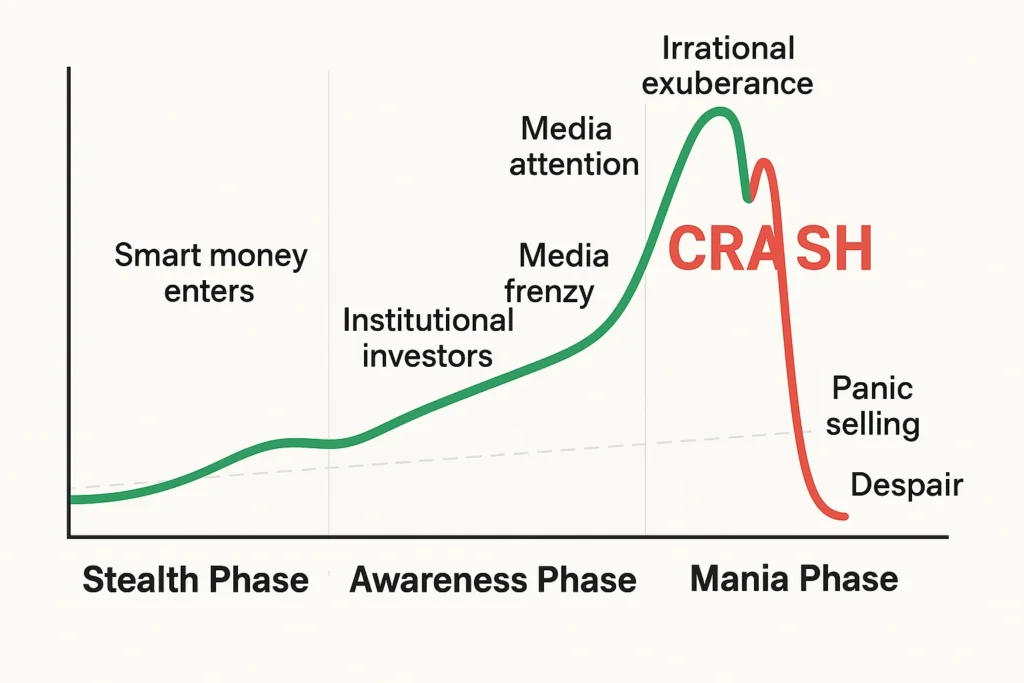

A financial crash is more than just a bad day on Wall Street; it’s a systemic rupture. Imagine a crowd suddenly stampeding for a single exit—prices don’t just fall, they gap down as sell orders massively overwhelm buys, liquidity evaporates, and fear becomes the only fundamental. It’s the violent popping of a speculative bubble, where assets valued on future dreams collide with present-day reality. These events reset valuations, wipe out leveraged wealth, and can trigger or exacerbate broader economic recessions, impacting everything from retirement accounts to Main Street businesses.

Key Takeaways

The Core Concept Explained

A financial crash measures the violent unwinding of market confidence. It’s not defined by a specific percentage drop but by the nature of the decline: extreme velocity, high volume, and systemic impact. A high-value, sustained market downturn becomes a crash when it triggers a self-reinforcing cycle of margin calls (forcing leveraged investors to sell), fund redemptions, and panic among retail investors. This transforms a correction into a collapse. The key indicator is a breakdown in market microstructure—the normal functioning of buyers and sellers—leading to disorderly price discovery.

How is a Financial Crash Identified

Since there’s no single formula, a crash is identified by observing a confluence of qualitative and quantitative thresholds being breached in a short timeframe.

Key Identification Metrics

- Magnitude of Decline: A drop of 20% or more in a major broad-market index (like the S&P 500, DJIA, or FTSE 100) from a recent peak. This is the technical definition often used.

- Velocity of Decline: The speed is critical. A 20% drop over 12 months is a bear market; a 20% drop in a matter of days or weeks signals a crash.

- Breadth of Decline: The sell-off is not isolated. It affects the vast majority of stocks across sectors, not just a few overvalued tech names.

- Volume & Volatility Spikes: Trading volume surges to multi-year highs as panic sets in. The CBOE Volatility Index (VIX), known as the “fear gauge,” spikes dramatically.

- Liquidity Dry-Up: Bid-ask spreads (the difference between buying and selling prices) widen significantly, indicating a lack of willing buyers.

For a US investor watching the S&P 500, a swift fall from 4,800 to below 3,840 would trigger crash alerts. Similarly, a UK investor would monitor the FTSE 100, while those in Canada and Australia track the S&P/TSX and ASX 200, respectively. Regulatory bodies like the SEC or the FCA often issue statements during such events.

Why Understanding a Financial Crash Matters

Ignoring the possibility of a crash is like sailing without a lifeboat. Its importance is paramount for capital preservation—the first rule of investing.

- For Investors: It directly threatens long-term financial goals. A 50% crash requires a 100% return just to break even. Understanding crashes informs asset allocation (the mix of stocks, bonds, cash) and the necessity of diversification across uncorrelated assets. It’s the primary reason for holding “safe haven” assets like Treasury bonds or gold.

- For Traders: Crashes present extreme volatility, which means high risk but also potential for high reward for those with strict risk management. Strategies like short-selling, buying put options, or trading volatility products (like VIX futures) become highly relevant. Knowing crash dynamics helps identify potential climax sell-offs or “capitulation,” which can signal a bottom.

- For Everyone: Crashes have real economic consequences, potentially leading to recessions, job losses, and changes in monetary policy (like the Federal Reserve cutting interest rates). This affects business decisions, real estate values, and overall economic confidence.

How to Use Crash Awareness in Your Strategy

Use Case 1: Defensive Portfolio Construction (The “Sleep at Night” Portfolio)

- Action: Allocate a portion of your portfolio to non-correlated or negatively correlated assets before a crisis. This includes long-term government bonds (e.g., US Treasuries, UK Gilts), gold, and defensive sector ETFs (consumer staples, utilities). A classic 60/40 stock/bond portfolio is designed to mitigate crash impacts.

- Resource: To build a resilient portfolio, you need a platform that offers a wide range of ETFs and bonds. [We review the best brokers for long-term investors here].

Use Case 2: The “Crash Checklist” for Emotional Discipline

- Action: Write down your rules in advance. For example: “If the S&P 500 falls 20% in a month, I will: 1) Rebalance my portfolio to my target allocation (which may mean buying stocks), 2) NOT check my account daily, 3) Review my financial plan, not my portfolio.” This turns panic into a planned procedure.

Use Case 3: Identifying Potential Buying Opportunities (For the Experienced)

- Action: After a severe crash, valuations become compelling. However, “catching a falling knife” is dangerous. Look for signs of stabilization: decreasing volume on down days, failed attempts to make new lows, and extreme negative sentiment readings. Dollar-cost averaging into a broad-market index fund can be a prudent way to start.

- Promotes Risk Management: Forces planning for worst-case scenarios, leading to more robust portfolios.

- Provides Historical Context: Reveals common patterns (leverage, speculation) to identify present-day excess.

- Creates Bargain Opportunities: Resets valuations, creating potential generational buying points for prepared investors.

- Encourages Long-Term Thinking: Reinforces that surviving downturns is critical to long-term compounding wealth.

- Improves Emotional Resilience: Knowing crashes are part of the cycle helps prevent panic selling at the bottom.

- Predictive Impotence: Identifying vulnerable conditions is possible, but timing the exact trigger is notoriously futile.

- Can Lead to Permanent Pessimism: May cause underinvestment, resulting in significant missed bull market gains (opportunity cost).

- Every Crash is Unique: Relying solely on historical analogies can be misleading as catalysts and contexts differ.

- May Encourage Market Timing: The desire to avoid a crash can tempt investors into a strategy proven to fail for most.

- Psychological Burden: Constant vigilance can create unnecessary stress, counter to sound financial planning.

Building a Crash-Resistant Portfolio: A Step-by-Step Framework

This goes beyond theory into actionable steps any investor can take.

Step 1: Conduct a Personal Risk Audit.

- Action: List all your liabilities and near-term (3-5 year) cash needs (mortgage, tuition, living expenses). Compare this to your stable assets (cash, bonds). The gap is your “risk exposure.” Your equity allocation should not bridge this gap.

Step 2: Implement Non-Correlated Asset Allocation.

- Action: Allocate by purpose, not just percentage. For example:

- Stability Layer (40%): Short-to-intermediate term government bonds (e.g., US Treasuries, UK Gilts). These often rise during equity crashes as investors flee to safety.

- Growth Layer (50%): A globally diversified mix of low-cost stock index funds (e.g., S&P 500, FTSE All-World). This is your long-term engine.

- Insurance Layer (10%): True diversifiers like physical gold (via ETFs like GLD), Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), or managed futures funds. These act as “portfolio airbags.”

Step 3: Use “Circuit Breakers” in Your Plan.

- Action: Set automatic, non-emotional rules. Example: “If my total portfolio value drops by 15%, I will automatically rebalance back to my target allocation.” This forces you to buy assets when they are cheap and sell assets that have held up, locking in a disciplined “buy low, sell high” mechanism.

Behavioral Pitfalls to Avoid During a Crash

Recognizing psychological traps is half the battle.

- The Narrative Fallacy: As the crash unfolds, a clear, simple story emerges (e.g., “The banks are finished,” “Tech is dead”). Our brains crave these stories, but they lead to extrapolating the current trend indefinitely. Antidote: Focus on long-term historical data, not the day’s headlines.

- Loss Aversion in Overdrive: The pain of losses is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gains. In a crash, this can make selling to “stop the pain” feel like a physical necessity. Antidote: Have your investment policy statement written and accessible. Follow the process, not your gut.

- Confirmation Bias Seeking: You’ll actively seek out media and commentators who confirm your worst fears, reinforcing the panic. Antidote: Deliberately seek out balanced, long-term optimistic views (from credible sources) to challenge the dominant narrative.

- Action Bias: The feeling that you must do something. This leads to selling at lows or making poorly-timed, speculative bets to “recoup losses quickly.” Antidote: Remember that for a long-term investor, sometimes the most powerful action is strategic inaction.

Financial Crash in the Real World: The 2008 Global Financial Crisis

The 2007-2008 crisis is a quintessential modern financial crash. It began with a bubble in US housing prices, fueled by lax lending standards and the securitization of subprime mortgages into complex products (CDOs) sold globally. When homeowners began defaulting, these assets plummeted in value.

The crash climaxed in September 2008 with the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, a major global investment bank. This triggered a full-blown liquidity crisis—banks stopped trusting each other and lending froze. The S&P 500 plunged over 50% from its 2007 peak. The contagion spread worldwide, requiring unprecedented government and central bank interventions (TARP, quantitative easing) to prevent a total collapse of the financial system. It was a crash rooted in excessive leverage, flawed risk models, and regulatory failure, demonstrating the systemic interconnectedness of modern finance.

For US and UK audiences, this was a direct, life-altering event, with major institutions like AIG, RBS, and HBOS requiring bailouts. The aftermath led to sweeping regulatory changes like the Dodd-Frank Act in the US, which still impacts investors and traders today.

The Role of Central Banks & Government: A Post-2008 Landscape

Since 2008, the playbook for managing crashes has evolved. Understanding this can help you interpret events.

- The “Fed Put” (and other Central Banks): The implicit belief that the U.S. Federal Reserve (and the Bank of England, ECB, etc.) will intervene with monetary policy (rate cuts, quantitative easing) to stem a market free-fall. This has created a moral hazard but is a modern market reality.

- Macroprudential Regulation: Post-2008 reforms like stress tests for banks (Dodd-Frank Act in the US) and higher capital requirements aim to make the financial system itself more shock-absorbent, potentially reducing the severity of future crashes.

- What This Means for You: While these tools may reduce systemic risk, they can also distort asset prices and create new bubbles in different areas (e.g., corporate debt, real estate). It underscores that crashes may manifest differently in the future, not that the cycle is abolished.

Financial Crash vs Bear Market vs Market Correction

| Feature | Financial Crash | Bear Market | Market Correction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition & Decline | Sudden, severe, systemic collapse (>20% drop rapidly). | Prolonged decline of 20%+ from a high over months/years. | Short-term decline of 10-20% from a recent high. |

| Primary Cause | Systemic failure, liquidity crisis, catastrophic bubble burst. | Economic recession, rising rates, sustained loss of confidence. | Profit-taking, short-term fear, overbought conditions. |

| Duration & Speed | Very short (weeks/months), but impact is long-lasting. | Extended period (often 12-18 months on average). | Short-lived (weeks to a few months). |

| Investor Psychology | Panic & Capitulation: Desire to exit at any price. | Pessimism & Despair: Grinding loss of hope. | Worry & Caution: Healthy reassessment of risk. |

| Recovery Implication | Often requires major policy intervention; recovery path is uncertain. | Recovery begins with economic improvement and renewed confidence. | Typically a healthy reset within an ongoing bull market trend. |

Conclusion

Ultimately, understanding financial crashes is not about predicting doom but about building resilience. It’s the financial equivalent of installing smoke detectors and having an escape plan—you hope never to use them, but their presence is critical for survival. As we’ve seen, crashes are destructive but also cyclical; they wipe out speculative excess and, for the prepared, create opportunity. The key is to let this knowledge inform your strategy—through diversification, asset allocation, and emotional discipline—rather than dictate it through fear. By incorporating crash awareness into a long-term, process-driven plan, you can navigate market extremes with greater confidence and protect your most important asset: your capital.

Ready to build a crash-resistant portfolio? The foundation is a reliable brokerage platform with access to diverse assets, from ETFs to bonds. We’ve meticulously reviewed and ranked the best online brokers for long-term investors to help you get started on solid ground.

Related Terms:

- Bear Market: The broader, often slower-moving downtrend of which a crash can be the violent initiating event.

- Recession: A significant decline in general economic activity (GDP, income, employment). A severe financial crash can cause a recession, and a deep recession can worsen a bear market.

- Black Swan Event: A term popularized by Nassim Taleb for an extremely rare, unpredictable event with severe consequences. A financial crash can be the result of a Black Swan (e.g., a pandemic) or can itself be considered a Black Swan due to its impact.

- Margin Call: A broker’s demand for an investor to deposit more money when the value of their leveraged account falls. A cascade of margin calls is a key accelerator of a crash.

- Volatility Index (VIX): The “fear gauge” that measures expected market volatility. It typically spikes to extreme levels during a crash.

Frequently Asked Questions About Financial Crashes

Recommended Resources

- The Defensive Investor’s Guide to Asset Allocation

- Bear Market Investing Strategies: What to Do When Markets Fall

- How to Read Market Sentiment Indicators

- The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – Investor Education

- Federal Reserve History

- Academic Paper (Seminal): The Crash of 2008: Causes and Lessons by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).