What Is Amortization Loan Repayment, Schedules, and Formulas

Amortization is the process of gradually paying down a debt through scheduled, periodic payments that apply to both principal and interest. It’s the financial engine behind most loans and mortgages, dictating your payment schedule and how you build equity over time. Understanding amortization is crucial for anyone with debt or considering a loan, as it reveals the true cost of borrowing and your path to ownership.

Summary Table

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Definition | Amortization breaks down a loan into consistent, periodic payments throughout the duration of the loan. |

| Also Known As | Loan amortization, debt amortization |

| Main Used In | Mortgages, Auto Loans, Personal Loans, Business Loans, Accounting. |

| Key Takeaway | Early payments are mostly interest, while later payments are mostly principal. |

| Formula | Monthly Payment (PMT) = P [r(1+r)^n]/[(1+r)^n – 1] |

| Related Concepts |

What is Amortization

Within the realm of finance, amortization refers to the methodical paydown of borrowed capital across a predetermined schedule. Each payment you make is split into two parts: one portion covers the interest charged for that period, and the remaining portion reduces the original amount you borrowed (the principal). An amortization schedule is a complete table of these periodic payments, showing the exact breakdown of interest and principal for every payment until the loan is paid off.

Key Takeaways

The Core Concept Explained

The core concept hinges on the relationship between principal and interest. Since the original loan amount is at its maximum when you first borrow, the interest fees charged on that sizable balance are consequently largest at the start. As a result, your fixed payment is mostly interest with only a small chunk going toward the principal.

Each successive payment reduces the remaining loan balance. This declining principal results in lower interest being accrued for each subsequent period. Consequently, a growing fraction of the unchanging payment amount is freed up to directly reduce the principal debt. This creates a snowball effect, accelerating the pace at which you build equity in an asset (like a house) over the life of the loan.

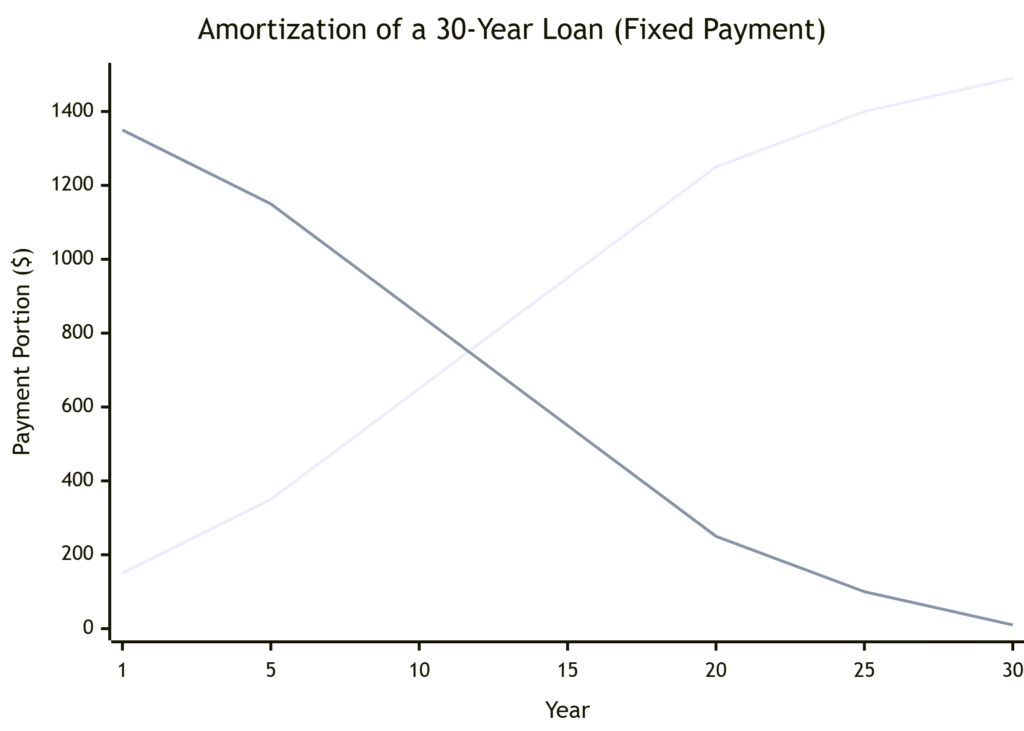

The chart below visualizes how each fixed payment is split between interest and principal over the life of a 30-year mortgage. Over the life of the loan, observe the inverse relationship where the interest component diminishes as the share applied to the principal grows.

In this example, the total payment remains constant, but the allocation shifts dramatically.

How to Calculate Amortization

The most common calculation is determining the fixed monthly payment required to fully amortize a loan over its term. This is done using the amortization formula.

Step-by-Step Calculation Guide

You can determine the consistent monthly payment amount, often denoted as PMT, using this standard equation:

PMT = P × [ (r(1+r)^n) / ((1+r)^n – 1) ]

Where:

- P = The initial principal loan amount (e.g., $300,000)

- r = The monthly interest rate (Annual rate ÷ 12). For a 4% annual rate, r = 0.04 / 12 = 0.003333

- n = The overall count of payments is calculated by multiplying the loan’s term in years by twelve.. For a 30-year loan, n = 30 × 12 = 360

Example Calculation:

Consider this example: determining the monthly installments for a 30-year, $300,000 home loan with a 4% yearly interest rate.

- Input Values:

- P = $300,000

- r = 4% / 12 = 0.04 / 12 = 0.003333

- n = 30 × 12 = 360

- Calculation:

- First, calculate (1 + r)^n: (1 + 0.003333)^360 ≈ 3.3135

- Then, r × (1+r)^n: 0.003333 × 3.3135 ≈ 0.011046

- Then, ((1+r)^n – 1): 3.3135 – 1 = 2.3135

- Finally, PMT = P × [result]: $300,000 × (0.011046 / 2.3135) ≈ $300,000 × 0.004774 = $1,432.25

- Interpretation:

The fixed monthly payment required to fully pay off this loan in 30 years is $1,432.25. This amount will remain unchanged, but its interest/principal composition will shift with each payment, as shown in the chart above.

Why Amortization Matters to Traders and Investors

- For Homebuyers & Borrowers: It is the roadmap to your debt freedom. An amortization schedule shows you the true cost of your loan, the total interest paid over decades can be staggering. It empowers you to see how making extra payments directly toward principal can shorten your loan term and save you thousands in interest.

- For Investors: Investors analyzing companies must understand loan amortization on the company’s debt to accurately assess its cash flow obligations and financial health.

- For Analysts: In corporate accounting, “amortization” also refers to the gradual write-down of an intangible asset’s value (like a patent or trademark) over its useful life. This is a key non-cash expense that affects a company’s reported earnings (net income) and must be added back to cash from operations on the cash flow statement, which is crucial for valuation.

How to Use Amortization in Your Strategy

- Use Case 1: The Power of Extra Payments. The most powerful application is making extra principal payments. Because the loan is amortized, every extra dollar paid toward principal reduces the balance immediately. This means all future interest calculations are on a lower balance, allowing you to pay off the loan years early.

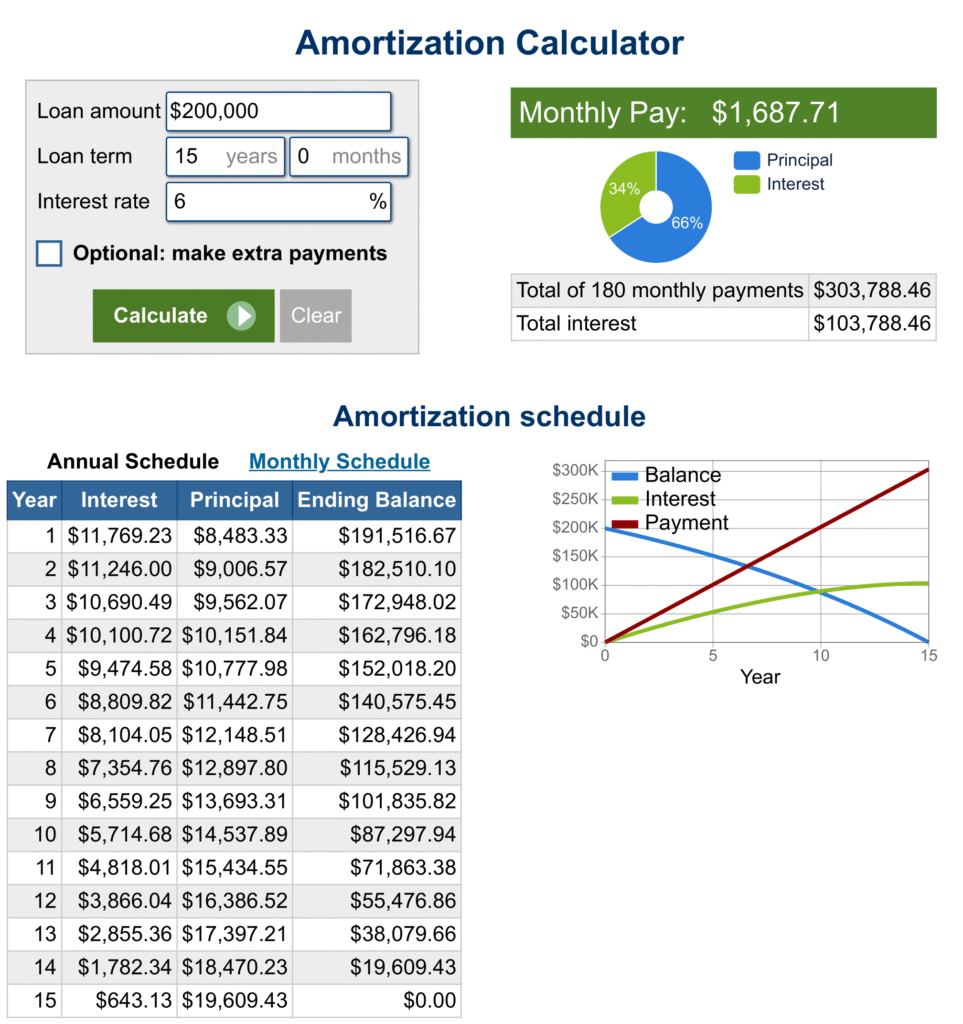

- Use Case 2: Comparing Loan Offers. Two loans can have the same interest rate but different terms. By reviewing an amortization table, you can contrast the cumulative interest of a 15-year loan with that of a 30-year loan, aiding in the selection of a mortgage that aligns with your financial objectives.

- Use Case 3: Refinancing Analysis. By comparing the remaining interest on your current amortization schedule to the total interest on a new proposed loan (minus fees), you can perform a break-even analysis to see if refinancing makes financial sense.

- Predictability: Fixed payments make budgeting easy and reliable for the life of the loan.

- Forced Discipline: The schedule ensures the loan will be paid off in full by the end of the term if all payments are made.

- Equity Building: It provides a clear, slow-but-steady path to building ownership in an asset.

- Front-Loaded Interest: The biggest drawback is that lenders collect most of their interest upfront, meaning you build equity very slowly in the early years.

- Less Flexibility: Fixed payment schedules are rigid. Missing payments can severely disrupt the amortization and lead to default.

- Doesn’t Account for Other Loan Types: This model does not apply to revolving debt (like credit cards) or interest-only loans.

Amortization in the Real World: A 30-Year Mortgage

A classic real-world example is a fixed-rate mortgage. Let’s take our $300,000 loan at 4% for 30 years.

- The First Payment: Your first payment of $1,432.25 is broken down as:

- Interest: $300,000 × (0.04/12) = $1,000.00

- Principal: $1,432.25 – $1,000.00 = $432.25

- New Balance: $300,000 – $432.25 = $299,567.75

- Payment #120 (Year 10): After 10 years, your balance is lower. The payment breakdown is now:

- Interest: ~$246,000 × (0.04/12) = $820.00

- Principal: $1,432.25 – $820.00 = $612.25

- The point at which your payment’s contribution to the principal surpasses the portion covering interest is a major milestone.

- The Final Payment: Your last payment of $1,432.25 will be almost entirely principal.

- The Shocking Stat: Over the 30-year life of this loan, you will have paid a total of $515,608.52. The $300,000 principal + $215,608.52 in interest. This stark reality is why understanding amortization is so critical.

Amortization vs Depreciation

The most common point of confusion is between Amortization and Depreciation.

| Feature | Amortization | Depreciation |

|---|---|---|

| What it applies to | Intangible Assets (loans, patents, trademarks) | Tangible Assets (machinery, vehicles, buildings) |

| Method | Typically uses the straight-line method (equal amounts per period). | Can use various methods (straight-line, declining balance, units of production). |

| Salvage Value | Usually amortized to a value of $0. | Often includes a salvage value (the estimated resale value at end of life). |

| Primary Use | Spreading loan costs or intangible asset costs. | Spreading tangible capital asset costs. |

Conclusion

Ultimately, understanding amortization provides a critical lens for evaluating the true cost and timeline of any debt, from a home mortgage to a business loan. While it appears as a simple mathematical calculation on paper, its real power lies in revealing the fundamental truth of long-term debt: you pay mostly interest first, and build equity slowly. As we’ve seen, amortization is not just a lender’s tool for predictable cash flow; it’s a borrower’s roadmap that shows exactly how each payment chips away at principal versus interest, empowering you to make smarter financial decisions—whether that’s evaluating the benefit of a refinance, understanding the impact of extra payments, or simply knowing when you’ll finally own that asset free and clear.

Related Terms:

- Depreciation: The equivalent concept for tangible physical assets.

- Principal: The original amount of money borrowed.

- Interest: The cost of borrowing that principal.

- Loan Term: The length of time over which the loan is amortized.

- Equity: The ownership value built through principal payments.

Frequently Asked Questions

Recommended Resources

- Investopedia: Amortization Definition and Examples

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB): What is an amortization schedule?

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC): Beginner’s Guide to Financial Statements (Covers amortization as an expense)

How did this post make you feel?

Thanks for your reaction!