What is Hedge Fund, How It Makes Money, Risks and Rewards

A hedge fund is a sophisticated, pooled investment vehicle that employs a wide range of complex and often aggressive strategies to generate high returns for its accredited investors. Unlike traditional mutual funds, they aim to “hedge” against market downturns and deliver positive returns in all market conditions, making them a powerful, albeit exclusive, tool for wealth generation.

For high-net-worth individuals and institutional investors in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, hedge funds represent a key component of advanced portfolio diversification, often operating through major financial hubs like New York and London.

Summary Table

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Definition | A privately owned, actively managed investment fund that uses advanced and diverse strategies, including leverage and derivatives, to generate high returns. |

| Also Known As | Alternative Investment Fund, Private Investment Partnership |

| Main Used In | Portfolio Management, Institutional Investing, High-Net-Worth Wealth Management |

| Key Takeaway | Hedge funds seek absolute returns (positive returns regardless of market direction) and have more flexibility than traditional funds, but they come with higher risk, higher fees, and less regulatory oversight. |

| Related Concepts |

What is a Hedge Fund

A hedge fund is an exclusive, actively managed partnership that pools capital from accredited investors to invest in a wide variety of assets. Think of it as a high-powered, nimble speedboat compared to the large, regulated cruise ship of a mutual fund. The core idea, originating from Alfred Winslow Jones in 1949, was to “hedge” the fund’s bets by combining long positions (buying stocks expected to rise) with short positions (selling borrowed stocks expected to fall). This was designed to deliver positive returns regardless of whether the overall market was going up or down. Today, the term encompasses a vast universe of funds using countless complex strategies far beyond simple hedging.

The Core Concept Explained

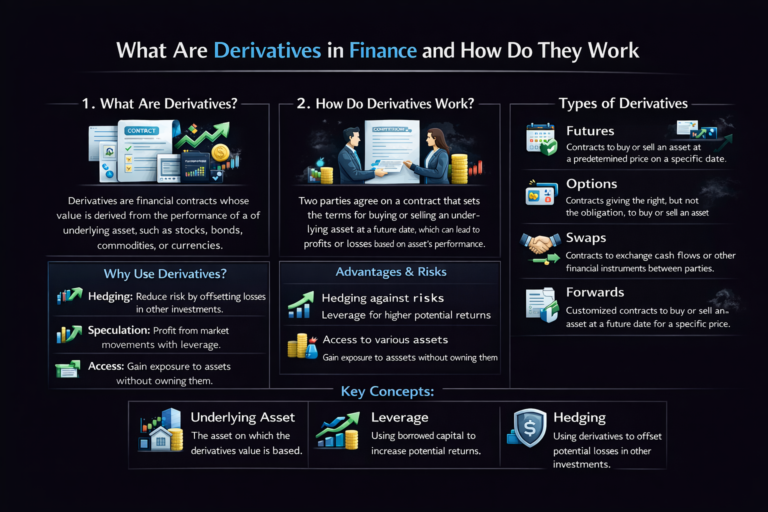

The core concept of a hedge fund is the pursuit of absolute returns. Unlike a mutual fund that aims to beat a benchmark index like the S&P 500 (a relative return), a hedge fund’s goal is to be profitable in all market environments—bull, bear, or sideways. To achieve this, fund managers have an extremely wide mandate. They can use leverage (borrowed money) to amplify gains, invest in derivatives like options and futures for sophisticated bets, take short positions to profit from falling prices, and trade in everything from currencies and commodities to complex structured products. This flexibility is their greatest strength but also the source of their significant risk.

Key Takeaways

How is a Hedge Fund Structured

While there’s no single “calculation” for a hedge fund, understanding its legal and financial structure is crucial. Most hedge funds are set up as Limited Partnerships (LPs) or Limited Liability Companies (LLCs). The investors are the Limited Partners, who provide the capital but have no role in management and their liability is limited to their investment. The hedge fund manager is the General Partner, who makes all the investment decisions and is personally liable for the fund’s debts.

The Accredited Investor Barrier

A key “input” into accessing a hedge fund is the investor’s status. In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) defines an accredited investor as an individual with:

- An annual income of at least $200,000 ($300,000 for joint income) for the last two years, with the expectation to earn the same or higher in the current year.

- Or a net worth exceeding $1 million, either alone or with a spouse (excluding the value of their primary residence).

This high barrier to entry is designed to ensure that investors have the financial sophistication and capacity to absorb potential losses.

For investors in the UK, the equivalent status is a “Sophisticated Investor” or “High-Net-Worth Investor” as defined by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), with similar criteria based on income and net worth.

Why Hedge Funds Matter to the Financial Ecosystem

Hedge funds play a significant and often controversial role in global finance. They are not just for the wealthy; their actions impact the entire market.

- For the Market: They provide liquidity by being active traders. Their research and large-scale bets can help make markets more efficient by quickly incorporating new information into asset prices. However, their use of leverage can also amplify market downturns.

- For Institutional Investors: Pension funds, university endowments, and insurance companies invest in hedge funds to diversify their portfolios. Because hedge fund returns are often uncorrelated with the stock market, they can potentially smooth out overall returns and reduce portfolio volatility.

- For High-Net-Worth Investors: They offer access to sophisticated, active management strategies that are unavailable to the general public, with the potential for outsized returns.

How to Use Hedge Fund Concepts in Your Strategy

While you may not be investing directly in a hedge fund, understanding their strategies can inform your own approach.

- Case 1: Understanding Hedging: The original concept of hedging—pairing a long position with a short one—can be applied on a smaller scale. For example, if you have a large concentration in tech stocks, you might buy a put option on the NASDAQ index to hedge against a sector-wide downturn.

- Case 2: The Importance of Due Diligence: Hedge fund investors perform intense due diligence on managers. Apply this same rigor to your own investments. Don’t just buy a stock based on a tip; research its fundamentals, management, and competitive landscape.

- Case 3: Considering Alternative Data: Many hedge funds use non-traditional data (satellite imagery, social media sentiment) for an edge. Retail investors can now access similar, though less sophisticated, data through various platforms to gauge company performance.

To start applying these advanced concepts, you’ll need a brokerage platform that offers robust tools like options trading and in-depth research. We’ve reviewed the best platforms for active traders to help you get started.

Common Hedge Fund Strategies

Beyond the general term, hedge funds are categorized by their specific strategies. Understanding these helps clarify their diverse risk-return profiles.

- Long/Short Equity: The most common strategy. Managers buy (go long) stocks they expect to rise and sell short stocks they expect to fall, aiming to profit from both sides and hedge against market moves.

- Global Macro: These funds make large, concentrated bets on macroeconomic trends in global markets. They might bet on interest rate changes, currency movements, or geopolitical events by trading bonds, currencies, and index futures.

- Event-Driven: This strategy seeks to profit from corporate events. This includes “merger arbitrage” (betting on the successful completion of mergers) and “distressed securities” (buying the debt of companies near or in bankruptcy).

- Quantitative: Also known as “quant funds,” these rely on complex mathematical models and algorithms to identify trading opportunities. They are typically market-neutral and execute a huge number of trades at high speeds.

Demystifying the 2 and 20 Fee Structure

The famous “2 and 20” fee model is a critical component of the hedge fund ecosystem.

- The 2% Management Fee: This is an annual fee based on the total assets under management (AUM). It covers the fund’s operational costs (salaries, office, data). If a fund has $1 billion in AUM, it earns $20 million per year in management fees, regardless of performance.

- The 20% Performance Fee: This is a fee taken from the fund’s profits. It aligns the manager’s incentive with the investors’ success. Crucially, most funds have a “hurdle rate” (a minimum return, often the risk-free rate) and a “high-water mark.” The high-water mark ensures that the manager only collects performance fees on new profits after recovering any previous losses for investors.

- High Return Potential: The use of leverage and aggressive strategies can lead to returns that significantly outpace the market.

- Portfolio Diversification: Their low correlation to traditional stock and bond markets can help reduce overall portfolio risk.

- Managerial Expertise: Access to some of the world’s most talented and well-resourced portfolio managers.

- Flexibility: Ability to profit in both rising and falling markets through short selling and other tactics.

- Absolute Return Focus: The goal is positive performance, not just beating a benchmark, which is appealing in bear markets.

- High Risk: The same strategies that create high returns can lead to devastating losses, especially when leverage is involved.

- High Fees: The “2 and 20” fee structure can consume a large portion of returns, making it hard to consistently outperform net of fees.

- Lack of Liquidity: Investments are often locked up for months or years, with limited windows for redemption.

- Lack of Transparency: Funds are not required to disclose their holdings publicly, so investors may not always know what they own.

- Regulatory Risk: Being less regulated means less protection for investors and potential for managerial misconduct.

Hedge Fund in the Real World: The LTCM Collapse

The story of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) is a classic case study of hedge fund potential and peril. Founded by Nobel laureates and renowned Wall Street traders, LTCM used incredibly complex arbitrage strategies to exploit tiny price discrepancies in bonds. For years, it generated massive returns.

However, LTCM employed enormous leverage—at one point, over $25 for every $1 of capital. When Russia defaulted on its debt in 1998, it triggered a global flight to quality that LTCM’s models had deemed a near-impossibility. Their highly correlated bets all moved against them at once. The fund faced catastrophic losses, threatening to collapse the entire global financial system. The New York Fed had to orchestrate a $3.6 billion bailout by a consortium of major banks to prevent a market meltdown.

This event perfectly illustrates the “double-edged sword” of hedge funds: brilliant strategy, immense leverage, and a fatal blind spot to black swan events.

Hedge Funds vs Mutual Funds

A common point of confusion is the difference between hedge funds and other pooled investment vehicles like mutual funds and private equity.

| Feature | Hedge Fund | Mutual Fund |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Absolute Returns (positive in all markets) | Relative Returns (beat a benchmark index) |

| Investor Access | Accredited/Sophisticated Investors only | Open to the general public |

| Regulation | Lightly regulated (e.g., fewer disclosure requirements) | Heavily regulated (e.g., SEC regulations on liquidity, disclosure) |

| Fees | Performance-based (e.g., “2 and 20”) | Asset-based (e.g., Annual Management Fee) |

| Liquidity | Lock-up periods, limited redemptions | Daily liquidity |

Conclusion

Ultimately, understanding hedge funds provides a critical window into the high-stakes world of advanced finance. They are powerful vehicles for diversification and potential alpha generation, but they are not a magic bullet. As we’ve seen, their advantages—flexibility, high-return potential, and access to top talent—are counterbalanced by significant limitations like extreme risk, high fees, and illiquidity. For the vast majority of investors, direct investment may be out of reach or unsuitable. However, the core principles of seeking absolute returns, rigorous due diligence, and understanding the role of leverage are invaluable lessons that can be applied to any investment strategy. By appreciating what hedge funds are and how they operate, you become a more informed and sophisticated participant in the financial markets.

Ready to build a robust investment portfolio? While hedge funds might be a future consideration, starting with a solid foundation is key. We recommend educating yourself further through authoritative sources like the SEC’s educational page on Hedge Funds to continue your investment journey.

Related Terms:

- Private Equity: Similar to hedge funds in being a private, alternative investment, but private equity typically invests directly in companies to restructure them over a long horizon (5-10 years), whereas hedge funds trade more liquid securities.

- Fund of Funds (FOF): A fund that invests in a portfolio of other hedge funds, aiming to provide diversification across managers and strategies.

- Leverage: The use of borrowed money to amplify investment returns, a cornerstone of many hedge fund strategies.

- Derivatives: Financial contracts like options and futures whose value is derived from an underlying asset, widely used by hedge funds for hedging and speculation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Recommended Resources

- The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s Investor Bulletin on Hedge Funds provides an excellent, unbiased regulatory perspective.

- Investopedia’s Hedge Fund Section offers a deep dive into specific strategies and terminology.

- The book “The Big Short” by Michael Lewis, while about the 2008 crisis, offers a thrilling look into the mindset and strategies of hedge fund managers who bet against the housing market.