What Is Depreciation, How It's Calculated, Why Investor Care

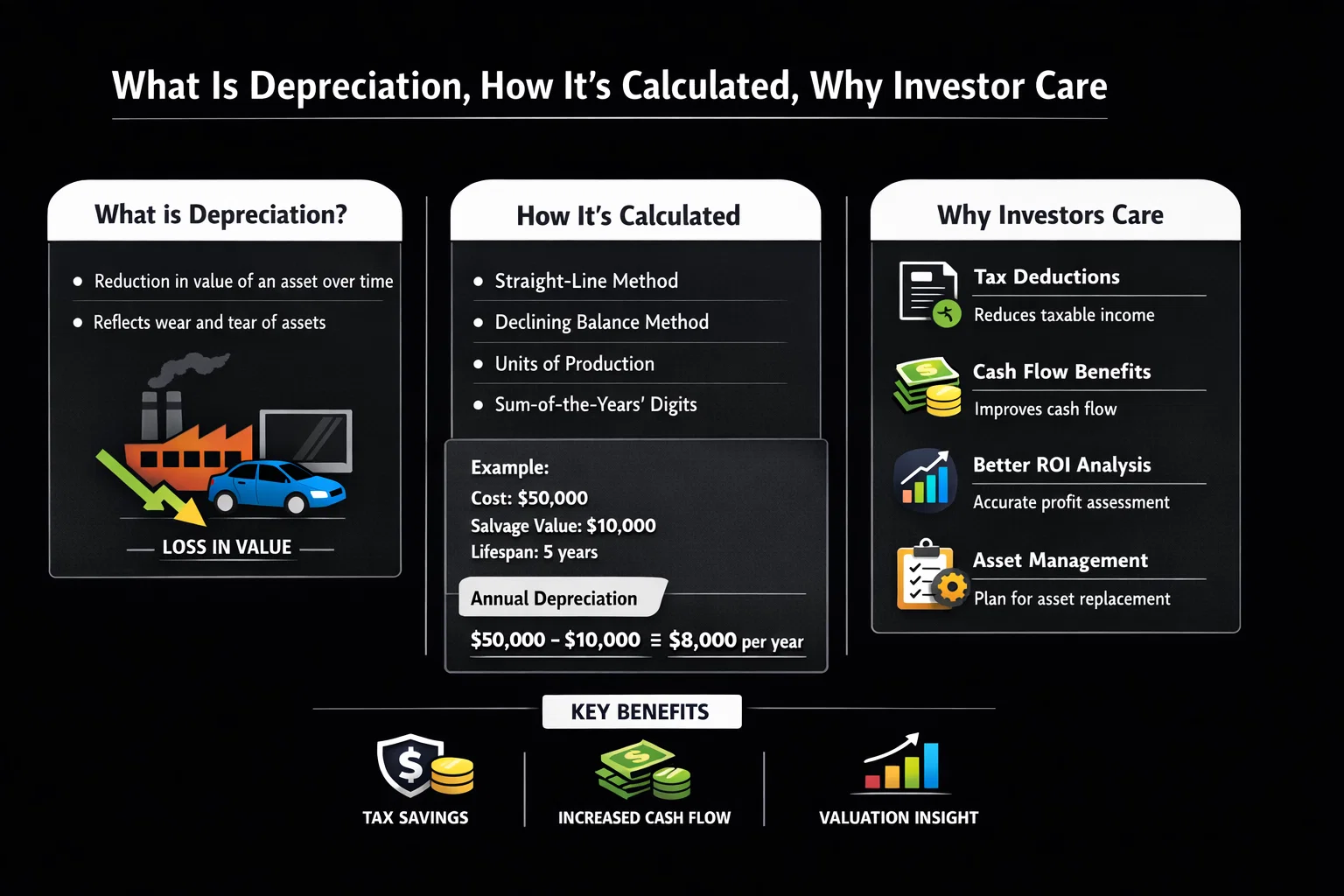

Depreciation is the systematic allocation of an asset’s cost over its useful life, reflecting how it loses value through wear, tear, and obsolescence. It’s a fundamental accounting concept that transforms large capital expenditures into manageable expenses, directly impacting a company’s financial health, tax obligations, and an investor’s understanding of true profitability. For investors analyzing stocks on the NYSE or NASDAQ, and for business owners navigating IRS rules, mastering depreciation is non-negotiable.

For investors and business owners in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, depreciation is a critical factor in financial analysis and tax strategy. Understanding GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) rules in the US or IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) in other regions is essential for accurate valuation and compliance with bodies like the SEC, HMRC, or the ATO.

Summary Table

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Definition | The accounting method of allocating the cost of a tangible asset over its estimated useful life. |

| Also Known As | Capital Cost Allowance (CCA, primarily in Canada), Amortization (for intangible assets), Wear and Tear. |

| Main Used In | Corporate Accounting, Financial Analysis, Investment Research, Tax Planning, Business Valuation. |

| Key Takeaway | Depreciation is a non-cash expense that reduces reported earnings but conserves cash, making it crucial for understanding a company’s true operating performance and cash flow. |

| Formula | Depreciation Expense = (Cost of Asset – Salvage Value) / Useful Life |

| Related Concepts |

What is Depreciation

Imagine buying a delivery van for your business. The van loses value the moment you drive it off the lot and continues to do so each year due to use, mileage, and newer models. Depreciation is the accounting process that captures this decline in value. Instead of taking the entire cost as an expense in the year of purchase—which would severely understate profits that year—you spread the cost over the van’s expected service period (e.g., 5 years). This matching principle ensures expenses are recognized in the same period as the revenue the asset helps generate.

The Core Concept Explained

Depreciation doesn’t track the asset’s market value (which can fluctuate unpredictably) but rather its theoretical consumption. It measures how much of an asset’s economic usefulness has been used up in a given accounting period. A high annual depreciation expense indicates a significant investment in assets that are being consumed quickly, common in tech or transportation. A lower expense might suggest older assets, longer useful lives, or a capital-light business model.

Key Takeaways

How is Depreciation Calculated

The most common formula for the Straight-Line method is:

Depreciation Expense = (Cost of Asset - Salvage Value) / Useful Life

Step-by-Step Calculation Guide

Let’s break down the components using an example relevant to a US-based company:

- Cost of Asset: The total amount paid to acquire and prepare the asset for use (purchase price + taxes + delivery + installation). Example: A CNC machine costs $110,000.

- Salvage Value: The estimated resale value at the end of its useful life. Example: The machine is expected to be sold for scrap for $10,000.

- Useful Life: The estimated time period the asset will be productive for the business. This is guided by IRS guidelines (e.g., Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System – MACRS) or management’s estimate. Example: 5 years.

Example Calculation:

Depreciation Expense = ($110,000 - $10,000) / 5 years = $20,000 per year.

| Year | Beginning Book Value | Depreciation Expense | Accumulated Depreciation | Ending Book Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $110,000 | $20,000 | $20,000 | $90,000 |

| 2 | $90,000 | $20,000 | $40,000 | $70,000 |

| 3 | $70,000 | $20,000 | $60,000 | $50,000 |

| 4 | $50,000 | $20,000 | $80,000 | $30,000 |

| 5 | $30,000 | $20,000 | $100,000 | $10,000 (Salvage Value) |

Interpretation: The company recognizes a $20,000 expense annually for five years, reducing its pre-tax income by that amount and lowering its tax bill. The asset’s book value on the balance sheet declines to its salvage value.

When analyzing a UK-listed company on the LSE, you might see depreciation calculated per IFRS guidelines, while a Canadian company reports CCA for tax purposes under the CRA. Always check the accounting standards used in the financial statements’ notes.

Alternative Depreciation Methods

While straight-line depreciation is the most common and simplest method, businesses often use alternative approaches to better match expense recognition with an asset’s actual usage patterns or economic benefits.

Declining Balance Method

How it works: Applies a constant depreciation rate to the asset’s book value at the beginning of each period, resulting in higher expenses in early years.

Formula: Depreciation Expense = Book Value at Beginning of Year × Depreciation Rate

Common Variant: Double-Declining Balance (DDB) uses a rate that’s double the straight-line rate.

Best for: Assets that lose value quickly in early years (vehicles, computers, technology).

- Year 1: $10,000 × 40% = $4,000

- Year 2: ($10,000 – $4,000) × 40% = $2,400

- Year 3: ($6,000 – $2,400) × 40% = $1,440

Units of Production Method

How it works: Ties depreciation directly to usage or output. You calculate a depreciation rate per unit, then multiply by actual units produced/used in the period.

Formula: Depreciation Expense = [(Cost – Salvage Value) / Total Estimated Units] × Units Produced in Period

Advantage: Most accurately matches expense with revenue generation.

Best for: Manufacturing equipment, mining machinery, vehicles with usage-based wear.

- Depreciation per unit = ($50,000 – $5,000) / 100,000 = $0.45/unit

- If 12,000 units produced this year: $0.45 × 12,000 = $5,400 depreciation

Tax Note: For US tax purposes, the IRS generally requires use of MACRS (Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System), which is an accelerated method with specific recovery periods for different asset classes.

Why Depreciation Matters to Traders and Investors

- For Investors (Fundamental Analysis): Depreciation is key to calculating Free Cash Flow (FCF). You add depreciation back to net income as part of the cash flow statement’s operations section. A company with high depreciation and strong earnings may be generating significant hidden cash flow. It also affects valuation ratios like P/B (Price-to-Book).

- For Traders: Significant changes in a company’s depreciation policy or estimates (extending useful life) can be a “red flag” for earnings manipulation, potentially leading to volatility. Understanding this can help you anticipate market reactions to earnings reports.

- For Analysts: Depreciation is a major component of EBITDA. While useful, analysts must scrutinize it, as a company with aging assets may have low depreciation but looming large capital expenditures (CapEx) needs for replacements.

How to Use Depreciation in Your Strategy

Case 1: Identifying Cash Flow Strength

Look at the cash flow statement. If net income is low but cash from operations is high due to large add-backs for depreciation and amortization, the company’s core cash-generating ability might be stronger than the headline profit suggests. This is common in capital-intensive industries like telecoms or utilities.

Case 2: Spotting Aggressive Accounting

Compare a company’s depreciation methods and useful lives with its peers. If one company uses a much longer useful life for the same type of asset, it reports lower annual depreciation expense and higher current profits. This can be an aggressive accounting tactic that may unwind in the future.

Case 3: Evaluating Management’s Capital Discipline

Track the ratio of depreciation to capital expenditures (Depreciation / CapEx). A ratio consistently below 1.0 suggests the company is investing more in new assets than it is depreciating old ones, indicating growth. A ratio above 1.0 for a prolonged period might mean the company is under-investing, which could hurt future competitiveness.

- Tax Savings: Provides a legitimate tax deduction, conserving cash.

- Matches Expenses with Revenue: Follows the matching principle, giving a more accurate profit picture for each period.

- Funds Reinvestment: Cash conserved from the non-cash expense can support maintenance, debt repayment, or reinvestment.

- Simplifies Cost Allocation: Spreads the cost of a large asset over its useful life logically and consistently.

- Standardized Reporting: Governed by GAAP/IFRS, helping compare companies under the same accounting rules.

- Estimates Are Subjective: Useful life and salvage value are estimates; incorrect assumptions distort financials.

- Does Not Reflect Market Value: The book value after depreciation may not represent resale or replacement cost.

- Can Be Manipulated: Management may change estimates to influence reported earnings.

- Ignores Maintenance Costs: High depreciation doesn’t ensure maintenance or repair needs are covered.

- Complexity: Different methods (accelerated vs. straight-line) complicate cross-company comparisons without adjustments.

Depreciation’s Role in Different Industries: A Sector-by-Sector Analysis

Understanding how depreciation affects companies across different sectors is crucial for meaningful comparative analysis. Here’s how this non-cash expense plays out in key industries:

| Industry | Typical Assets Depreciated | Key Metric to Watch | Investor Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Servers, data centers, lab equipment, office tech | CapEx / Depreciation Ratio | A ratio < 1.0 may indicate under-investment in tech infrastructure or a shift to cloud (OpEx instead of CapEx). |

| Manufacturing & Industrials | Factories, machinery, assembly lines, robots | Depreciation / Sales | High ratio suggests capital intensity; compare with peers for efficiency. Watch for aging fleets needing replacement. |

| Telecommunications | Network towers, fiber cables, switching equipment | EBITDA Margin | High, stable depreciation is normal. Focus on EBITDA growth and FCF after maintenance CapEx. |

| Airlines | Aircraft, engines, flight simulators | Average Fleet Age | Older fleets = lower depreciation expense but higher fuel/maintenance costs. Balance is key. |

| Software & Services | Minimal PP&E; mostly computers & office equipment | Amortization of Intangibles | Depreciation is minor. Focus on amortization of acquired technology/customer lists. |

| Real Estate (REITs) | Commercial buildings, residential complexes | FFO (Funds From Operations) | REITs use FFO = Net Income + Depreciation (real estate). This is their key performance metric. |

Case Study: Comparing Two Retail Giants

Consider Amazon vs. a traditional retailer like Walmart. Amazon’s depreciation comes largely from its massive fulfillment centers and tech infrastructure. Walmart’s comes from stores and distribution centers. While both have high absolute depreciation, Amazon’s is growing faster as it builds out logistics networks, signaling aggressive expansion versus Walmart’s more mature, replacement-focused CapEx.

📊 Actionable Tip for Investors:

When analyzing a company, always check the “Property, Plant and Equipment” note in the financial statements. Look for:

- The depreciation method used (straight-line vs. accelerated)

- Useful life estimates for major asset classes

- Any changes in estimates (extending useful life boosts short-term earnings)

- Capitalized vs. expensed software development costs (critical for tech firms)

For US investors, resources like the SEC’s EDGAR database provide direct access to these notes.

Depreciation in the Real World: A Case Study

The Impact on a Giant: Boeing vs. Cash Flow

Aircraft manufacturers like Boeing provide a perfect case study. Building a 787 Dreamliner involves billions in capital expenditure. The tools, jigs, and factory equipment used to build these planes are depreciated over long periods. During the 737 MAX grounding and pandemic, Boeing’s profits were deeply negative. However, its cash flow statement showed that it still added back billions in depreciation each quarter. This highlighted that while its earnings were battered, a portion of its cash burn was not operational but related to halted deliveries and inventory buildup. For investors, this distinction—between accounting profit and cash flow—was crucial in assessing the company’s survival and recovery timeline.

Depreciation in Your Personal Finances & Small Business

Depreciation isn’t just for Fortune 500 companies—it’s a powerful tool for small business owners, freelancers, and even gig economy workers to reduce tax liability and understand true profitability.

Vehicle Depreciation for Gig Workers

Two Methods:

- Standard Mileage Rate (2024: $0.67/mile for US): Simple, IRS-published rate

- Actual Expense Method: Depreciate vehicle cost, plus deduct gas, repairs, insurance

Home Office & Rental Property

For Home Office: You can depreciate the portion of your home used exclusively for business.

For Rental Property: Residential buildings depreciate over 27.5 years (39 years for commercial). Only the building value—not land—is depreciable.

Equipment & Technology

Computers, cameras, specialized tools, and machinery used for business are depreciable.

Bonus: The IRS Section 179 deduction allows immediate expensing of up to $1.22 million (2024) of qualified business property in the year it’s placed in service, subject to limits.

Tax Strategy Corner: Depreciation Timing

Immediate Expensing (Section 179/Bonus)

- Benefit: Large upfront tax deduction

- Best for: High-income years, businesses expecting lower future income

- Consider: Creates lower basis for future depreciation

Accelerated Depreciation (MACRS)

- Benefit: Front-loaded deductions over several years

- Best for: Stable or growing businesses, maximizing mid-term deductions

- Consider: More complex record-keeping

Straight-Line Depreciation

- Benefit: Predictable, even deductions

- Best for: Consistent income, long-lived assets, simplicity

- Consider: Lower initial tax benefit

Ready to Implement?

Navigating depreciation for your business requires careful planning:

- Document Everything: Keep purchase receipts, invoices, and records of business use percentage.

- Separate Personal & Business: Use separate bank accounts and credit cards for clean record-keeping.

- Consult a Professional: Tax laws change frequently. A qualified CPA or tax advisor can help you maximize deductions while staying compliant with IRS or local tax authority rules.

Note: Tax rules vary by country. Always consult with a tax professional in your jurisdiction.

Depreciation vs Amortization

| Feature | Depreciation | Amortization |

|---|---|---|

| What it applies to | Tangible (Physical) Assets (e.g., machinery, vehicles, buildings) | Intangible Assets (e.g., patents, copyrights, goodwill, trademarks) |

| Cause of Expense | Wear and tear, obsolescence, usage. | Expiration of legal rights, consumption of economic benefits. |

| Common Methods | Straight-Line, Declining Balance, Units of Production. | Primarily Straight-Line; some exceptions for goodwill (impairment testing). |

| Residual Value | Often has a salvage value. | Often amortized to zero. |

| Example | A Tesla assembly robot. | The patent for a Pfizer drug formula. |

Conclusion

Ultimately, depreciation is far more than a technical accounting entry; it’s a critical lens for evaluating a company’s true economic reality. It sits at the intersection of profitability, cash flow, and capital management. While a powerful tool for tax savings and accurate reporting, its reliance on estimates means investors must remain vigilant. By learning to adjust earnings for depreciation, analyze its relationship with CapEx, and scrutinize a company’s depreciation policies, you can uncover deeper insights into operational health and management’s financial stewardship. Start by examining the “Property, Plant and Equipment” note in the next annual report you read.

Ready to put these concepts into action? The right tools are essential. We’ve meticulously reviewed and ranked the best online brokerage platforms for fundamental analysis to help you dig into financial statements with powerful screening tools.

Related Terms

- EBITDA: Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization. A key metric that adds depreciation and amortization back to earnings to show core operating cash profit.

- Capital Expenditures (CapEx): The cash outlay for new long-term assets. Depreciation is the subsequent expense recognition of past CapEx.

- Book Value (Carrying Value): The asset’s historical cost minus its accumulated depreciation. A key component of shareholder equity.

- MACRS: The Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System, the standard tax depreciation method mandated by the IRS for most US business assets.