Balance Sheet What It Is, How to Read, and Why It Matters for Investors

A balance sheet is a financial snapshot of a company at a single point in time, detailing what it owns, what it owes, and what is left for owners. For investors in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, analyzing this fundamental report is the first step toward assessing a company’s financial health and stability before committing any capital.

Geo-Targeting Prompt woven in: For investors in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, analyzing this fundamental report on companies listed on exchanges like the NYSE, NASDAQ, LSE, or ASX is the first step toward assessing financial health and stability before committing any capital.

Summary Table

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Definition | A financial statement that reports a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at a specific point in time. |

| Also Known As | Statement of Financial Position |

| Main Used In | Fundamental Analysis, Corporate Finance, Investment Research, Credit Analysis |

| Key Takeaway | It must always balance, following the core equation: Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity. |

| Formula | Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity |

| Related Concepts |

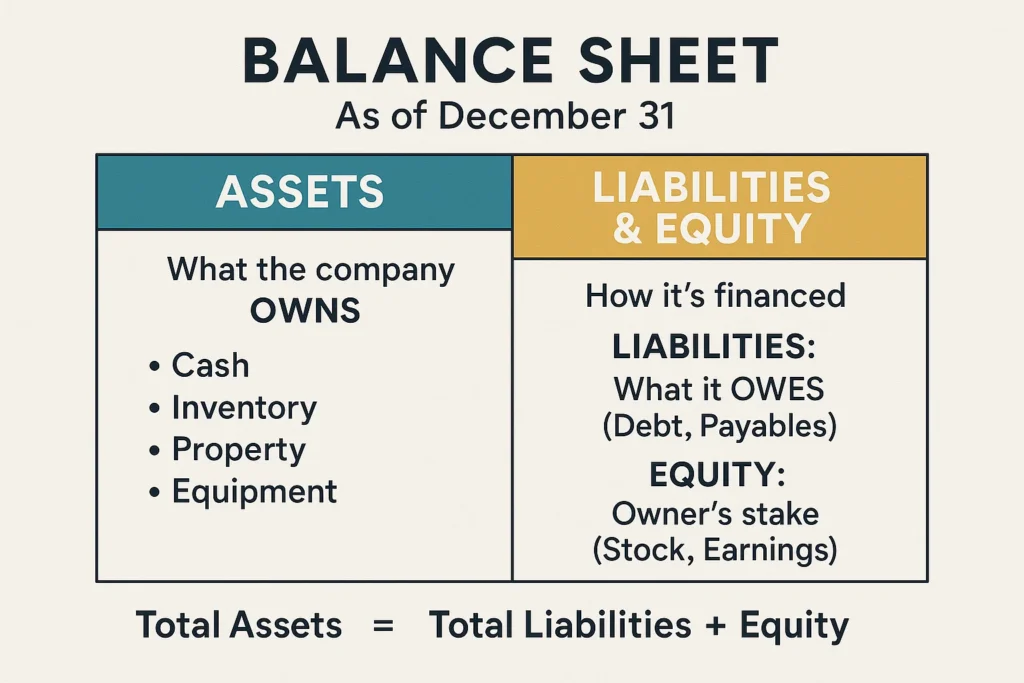

What is a Balance Sheet

A balance sheet is one of the three core financial statements used to evaluate a business. Think of it as a company’s financial report card at the end of a specific day—it doesn’t show the entire semester’s performance (like the income statement) or the cash movements (like the cash flow statement), but it tells you exactly where things stood on that date.

Imagine your own personal finances. Your Assets include your cash in the bank, your car, and your home. Your Liabilities are your mortgage, car loan, and credit card debt. Your Net Worth (or personal equity) is what’s left after you sell all your assets and pay off all your debts. A company’s balance sheet works the same way, where Shareholders’ Equity represents the company’s net worth.

Key Takeaways

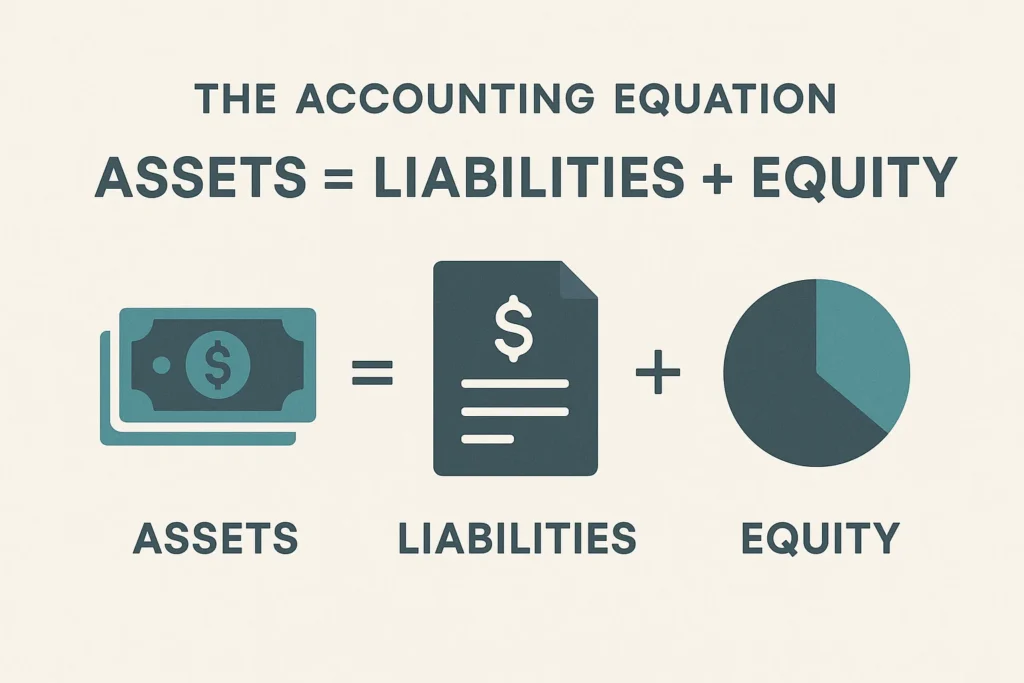

The Core Concept Explained

The balance sheet gets its name because it is a presentation of this perfectly balanced equation. The resources a company uses to operate (its assets) are always financed by either creditors (liabilities) or owners (equity). If this equation doesn’t hold, there is a fundamental error in the accounting.

A strong balance sheet typically features healthy cash reserves, manageable debt levels, and a growing equity base. A weak one might show high debt, declining cash, and negative retained earnings.

How a Balance Sheet is Structured

While not calculated in a single formula, the entire statement is built on the Accounting Equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity

Step-by-Step Breakdown

Each component is broken down into specific line items:

- Assets: Resources with economic value.

- Current Assets: Expected to be converted to cash within one year (e.g., Cash & Equivalents, Accounts Receivable, Inventory).

- Non-Current Assets: Long-term investments (e.g., Property, Plant & Equipment (PP&E), Patents, Goodwill).

- Liabilities: What the company owes to others.

- Current Liabilities: Due within one year (e.g., Accounts Payable, Short-Term Debt).

- Non-Current Liabilities: Long-term debts (e.g., Long-Term Debt, Bonds Payable).

- Shareholders’ Equity: The owners’ residual claim.

- Contributed Capital: Money invested by shareholders (e.g., Common Stock).

- Retained Earnings: Cumulative net income reinvested in the business, not paid out as dividends.

Example Balance Sheet: Apple Inc. (Simplified, in billions of USD)

| Assets | Liabilities & Equity |

|---|---|

| Current Assets | Current Liabilities |

|

Cash & Equivalents — $50 Marketable Securities — $40 Accounts Receivable — $30 Inventory — $10 Total Current Assets — $130 |

Accounts Payable — $60 Short-Term Debt — $20 Total Current Liabilities — $80 |

| Non-Current Assets | Non-Current Liabilities |

|

Property, Plant & Equipment — $40 Total Assets — $170 |

Long-Term Debt — $100 Total Liabilities — $180 |

| Shareholders’ Equity |

Common Stock — $50 Retained Earnings — ($60) Total Equity — ($10) Total Liabilities & Equity — $170 |

Note: This is a simplified, hypothetical example for illustration. In reality, Apple’s equity is positive. A negative equity, as shown here, could indicate significant cumulative losses.

Why the Balance Sheet Matters to Traders and Investors

- For Investors: It helps assess a company’s solvency (ability to meet long-term obligations) and financial stability. A company with little debt and plenty of cash is better positioned to survive economic downturns. It’s also used to calculate book value per share, a key metric for value investors.

- For Traders: While traders often focus on price action, a strong balance sheet can identify companies less likely to have a blow-up risk (e.g., bankruptcy). Positive balance sheet news (like a large cash position for a buyback) can be a catalyst for a price move.

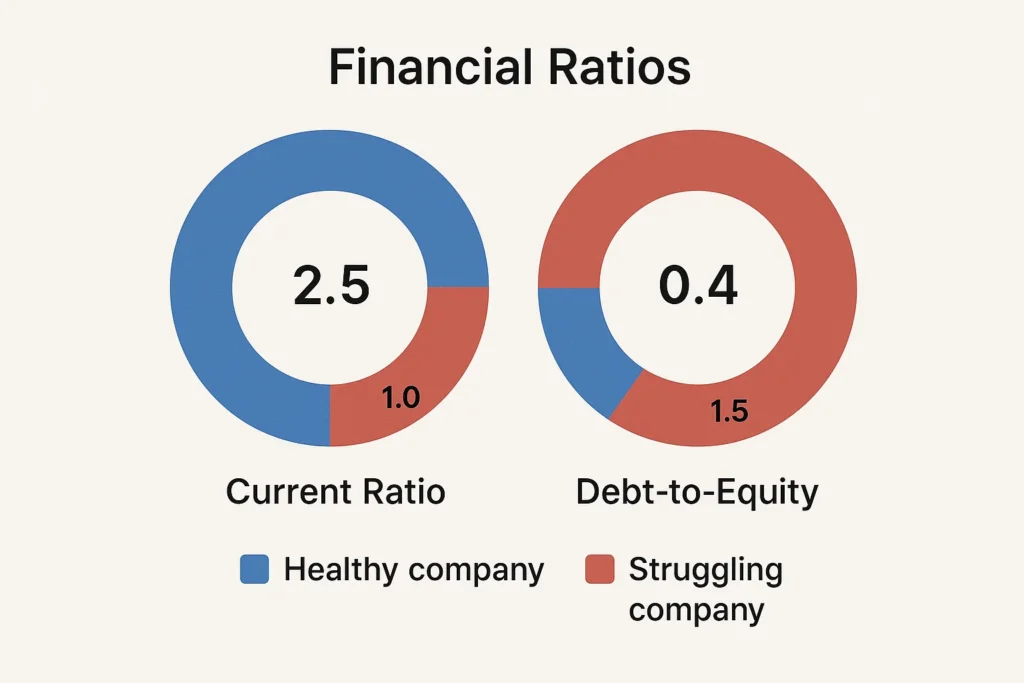

- For Analysts: It is the foundation for ratio analysis. Analysts use it to calculate liquidity ratios (Current Ratio), leverage ratios (Debt-to-Equity), and efficiency ratios (Inventory Turnover), providing a multi-faceted view of corporate health.

How to Use the Balance Sheet in Your Investment Strategy

Use Case 1: Screening for Safe Dividend Stocks

Look for companies with a low Debt-to-Equity Ratio and ample Cash & Equivalents. This indicates they can sustain dividend payments even during hard times without taking on excessive debt.

Use Case 2: Identifying Undervalued Companies (Value Investing)

Calculate the Book Value per Share (Total Equity / Shares Outstanding). If the stock’s market price is trading below this book value, it might be undervalued, signaling a potential investment opportunity worthy of deeper research.

Use Case 3: Assessing Bankruptcy Risk (The Altman Z-Score)

This famous formula uses multiple balance sheet and income statement values to predict the likelihood of corporate bankruptcy. A low Z-Score is a major red flag.

Analyzing these ratios manually can be time-consuming. To efficiently screen thousands of stocks based on balance sheet health, you need a powerful stock screening tool. We’ve reviewed the best platforms for fundamental analysis to save you time.

- Snapshot of Health: Provides a clear, quick view of a company’s financial strength at a glance.

- Basis for Ratios: Essential for calculating critical financial health metrics.

- Comparative Analysis: Allows for comparison between companies in the same industry.

- Credibility: Prepared according to standardized accounting principles (GAAP or IFRS), making them auditable and reliable.

- Historical Cost: Assets are typically recorded at their original purchase cost, which may not reflect their current market value. A piece of real estate bought 20 years ago could be worth 10x its book value.

- A Snapshot, Not a Movie: It does not show the flows of operations over a period. A company can have a great balance sheet on December 31st but have a terrible quarter.

- Intangibles are Hard to Value: The value of assets like brand reputation or intellectual property is often subjective and may not be accurately reflected.

- Open to Interpretation: Management decisions on inventory accounting (FIFO vs. LIFO) or depreciation methods can influence the numbers.

The 5-Minute Balance Sheet Health Check: A Practical Guide for Investors

You don’t need to be a CPA to spot warning signs or identify strengths on a balance sheet. Use this step-by-step checklist the next time you look at a company’s 10-K or 10-Q filing. We’ll use a hypothetical company, Innovate Corp. (listed on the NASDAQ), to illustrate.

The Quick-Check Dashboard:

| Step | What to Look For | Innovate Corp. Example (in millions USD) | Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The Liquidity Squeeze Test | Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities | $150 / $100 = 1.5 | ✅ Stable |

| 2. The Debt Burden Check | Total Debt / Total Assets | ($50 ST + $100 LT) / $500 = 0.3 or 30% | ✅ Manageable |

| 3. The Cash Safety Net | Cash & Equivalents vs. Short-Term Debt | $60 Cash vs. $50 ST Debt | ✅ Strong |

| 4. The Owner’s Stake | Trend of Shareholders’ Equity | Year 1: $200; Year 2: $240; Year 3: $280 | ✅ Growing |

Walk-Through of the Checklist:

- Step 1: The Liquidity Squeeze Test (Current Ratio)

- Why it matters: This tells you if the company can pay its bills coming due in the next year. A ratio below 1 is a major red flag, indicating potential liquidity problems.

- Interpretation: A ratio of 1.5 is generally considered healthy. It shows enough cushion without being so high that it suggests inefficiency (e.g., a ratio of 4 might mean too much cash sitting idle).

- Step 2: The Debt Burden Check (Debt-to-Assets Ratio)

- Why it matters: This measures leverage—what percentage of the company’s assets are financed by debt (as opposed to equity). A higher ratio means more risk, especially if interest rates rise.

- Interpretation: A ratio of 0.3 (30%) is conservative. For many industries, up to 0.5 (50%) is acceptable, but anything higher warrants a closer look, especially if the company isn’t highly profitable.

- Step 3: The Cash Safety Net (Cash vs. Short-Term Debt)

- Why it matters: This is a stress test. Can the company immediately pay off all its short-term debt without selling a single asset or earning another dollar?

- Interpretation: Innovate Corp. has more cash than short-term debt ($60m vs. $50m). This is a very strong sign of financial resilience. The opposite situation would be a significant concern.

- Step 4: The Owner’s Stake (Trend of Shareholders’ Equity)

- Why it matters: A consistently growing equity base, primarily through retained earnings, indicates a profitable company that is reinvesting in itself. A shrinking or negative equity is a massive warning sign.

- Interpretation: Innovate Corp.’s equity is growing steadily. This is the hallmark of a healthy, compounding business.

Performing this health check manually on dozens of stocks is tedious. To screen the entire market for companies that pass these criteria, you need a powerful stock screening tool. We’ve tested the best fundamental analysis screeners to help you automate this process.

Balance Sheet in the Real World: The Tale of Two Retailers

The 2017 bankruptcy of Toys R Us provides a stark lesson in balance sheet analysis. For years before its collapse, its balance sheet showed a massive amount of long-term debt (over $5 billion) that was used in a leveraged buyout. This debt load crippled its cash flow, as seen in the consistent negative retained earnings. Meanwhile, the current ratio was often below 1, indicating it struggled to pay its short-term bills with its short-term assets. An investor focusing on the balance sheet would have seen these red flags years in advance.

In contrast, Apple Inc. is renowned for its fortress-like balance sheet, often holding over $50 billion in cash and marketable securities with relatively modest debt. This immense liquidity provides a huge competitive advantage, allowing it to invest in R&D, weather economic storms, and return capital to shareholders through buybacks and dividends.

How Intangible Assets Are Reshaping the Modern Balance Sheet

The traditional balance sheet was built for industrial-age companies with physical assets. Today, for companies like Microsoft (software), Pfizer (pharma), or Meta (social media), the most valuable assets often aren’t factories but intellectual property. This creates a significant gap between a company’s book value and its market value. Here’s how accounting standards handle this.

The Great Divergence: Book Value vs. Market Value

- Book Value: The accounting value of equity from the balance sheet.

- Market Value: The total value of the company’s outstanding shares (Share Price x Shares Outstanding).

For S&P 500 companies, the market value is often 3-4x the book value. Why? Because the balance sheet, governed by US GAAP or IFRS, is terrible at capturing the value of internally generated intangible assets.

How GAAP and IFRS Treat Key Intangibles Differently:

| Intangible Asset | GAAP (Used in the US) | IFRS (Used in the UK, EU, etc.) | Impact on the Balance Sheet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research & Development (R&D) | Almost all R&D costs are EXPENSED immediately. This hits the income statement but does not create an asset. | Development costs can be CAPITALIZED as an asset if certain criteria are met (e.g., technical feasibility, intent to complete). | A UK-based tech company may have a higher asset base than an identical US company, making cross-border comparisons tricky. |

| Brand Value & Customer Lists | Only recognized as an asset if acquired in a business combination. Internally built brand value is never added to the balance sheet. | Same as GAAP for internally generated brands. IFRS is generally more permissive for capitalizing other internally generated intangibles. | The immense value of the Coca-Cola brand, built over a century, is not on its balance sheet. |

| Software Development | Costs are expensed until technological feasibility is established, after which they can be capitalized. | Similar to GAAP, but the criteria for capitalization can be less stringent, leading to more assets on the balance sheet. | A software company under IFRS might show more assets and higher equity than a comparable GAAP company, even if their products are identical. |

Why This Matters for Your Analysis:

- Don’t Over-rely on Book Value for Modern Companies: Using Price-to-Book (P/B) ratio to value a tech or biotech firm can be misleading. A high P/B doesn’t always mean overvalued; it may mean the company has valuable assets the balance sheet doesn’t show.

- Adjust Your Cross-Border Comparisons: When comparing a US pharmaceutical company (GAAP) to a European one (IFRS), remember that the European company will likely have a higher reported asset base and equity due to capitalized R&D. Their profitability (on the income statement) may also appear different.

- Look for Acquired Intangibles: When a company makes a large acquisition, the goodwill and other intangibles added to the balance sheet can give you a clue about the value of the target’s brands, patents, and technology. Scrutinize subsequent write-downs of these assets, as they signal the acquisition may not be paying off.

My Insight: The balance sheet is becoming less of a comprehensive statement of value and more of a historical record of tangible investments and acquisitions. The true value drivers for many of today’s most successful companies are now found in the footnotes and the income statement, in the form of sustained high profit margins and growth rates that their intangible assets generate.

Balance Sheet vs Income Statement

| Feature | Balance Sheet | Income Statement |

|---|---|---|

| What it measures | Financial Position | Financial Performance |

| Time Period | A Point in Time (e.g., Dec 31) | A Period of Time (e.g., Q1 2024) |

| Key Metrics | Assets, Liabilities, Equity | Revenue, Net Income, EPS |

| Primary Use | Assess Health & Stability | Assess Profitability |

Conclusion

Ultimately, the balance sheet is a non-negotiable tool for any serious fundamental analysis. It moves beyond mere profitability to answer critical questions about survival and stability. While it has limitations, such as its reliance on historical cost and its static nature, its power in revealing a company’s capital structure and liquidity is unmatched. By learning to calculate key ratios and read between the lines, you can identify both risky ventures and durable enterprises. Start by pulling up the latest 10-K or 10-Q filing for a company you’re interested in on the SEC’s EDGAR database and examine its statement of financial position for yourself.

Ready to put these concepts into action? The right tools are essential. We’ve meticulously reviewed and ranked the best online brokers for long-term investors to help you find a platform with robust fundamental analysis tools.

Related Terms

- Income Statement: Shows revenues and expenses over a period to determine profitability.

- Cash Flow Statement: Tracks the movement of cash from operating, investing, and financing activities.

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio: A key leverage ratio calculated directly from the balance sheet.

- Working Capital: The difference between Current Assets and Current Liabilities, a key liquidity measure.

- Book Value: The net asset value of a company, derived from Shareholders’ Equity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Recommended Resources

- SEC.gov EDGAR Database – To access the official filings (10-K, 10-Q) of any public US company.

- IFRS Foundation – For understanding the international accounting standards used in many countries outside the US.

- Corporate Finance Institute: Balance Sheet – For a deeper dive into advanced concepts.

How did this post make you feel?

Thanks for your reaction!